WHAT THE TRAIL FOUNDERS SAID-1921

Automobile travel in the northern or Panhandle district of Idaho and eastern Washington is one of the most delightful features of automobile travel anywhere in the country. In Idaho, the roads are mountain roads through the passes of the Bitter Roots and the Coeur D Alenes. All of it is very scenic.

Road conditions are generally good.

1921 Yellowstone Trail Touring Service

Map #8 of WA and ID

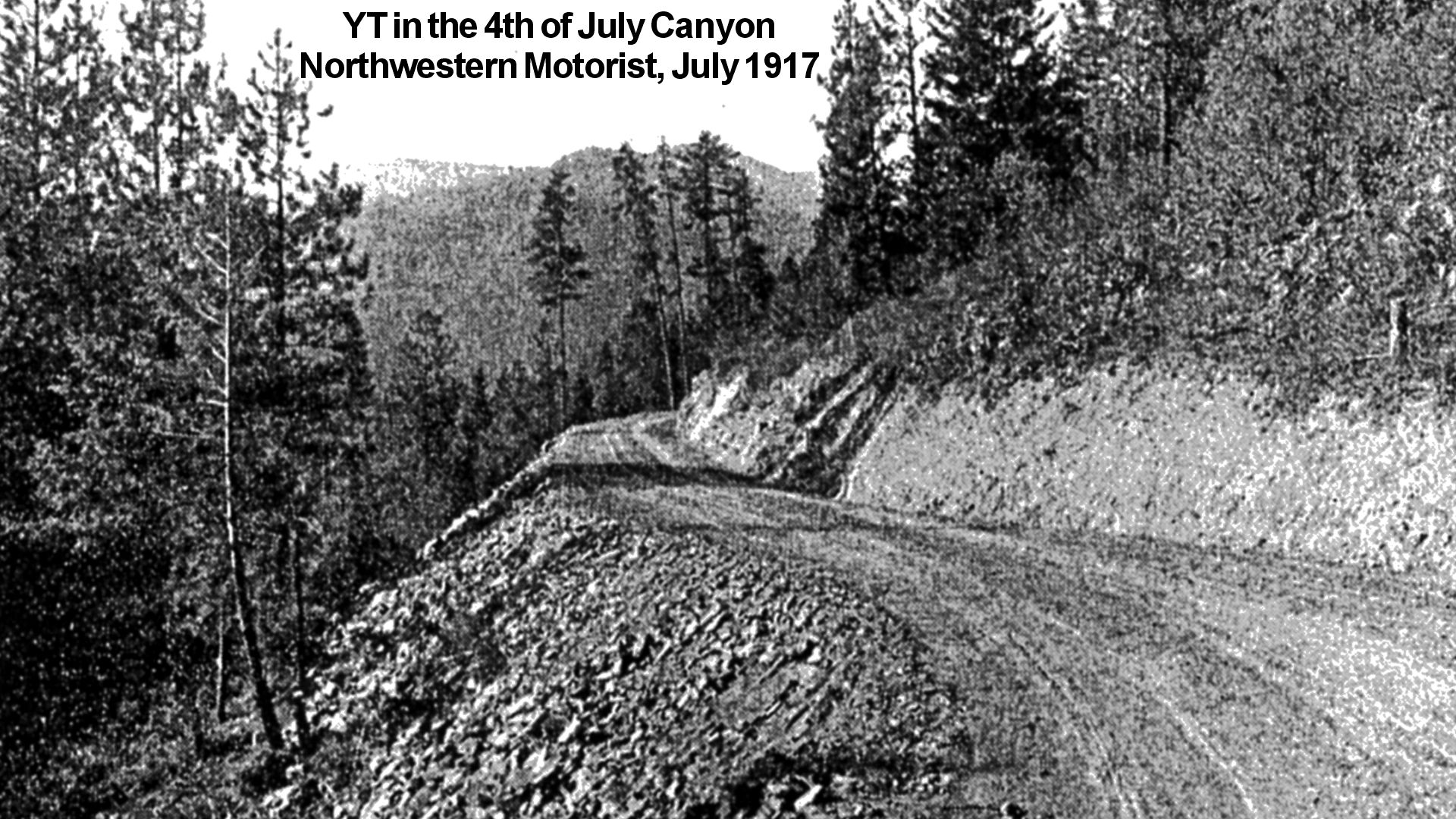

The 1919 Route Folder adds that from Couer d’Alene to the 4th of July Canyon there is a splendid road. Going east from the Canyon, a wonderful piece of road work is traveled here by cooperation of the state of Idaho, U.S. Forest Service and Kootenai and Shoshone Counties. Going east the Cataldo Mission, Wallace, and Mullan are reached on the road east where one is in the mining district. Mills are here in abundance, both ore and lumber.

The 1921 Route Folder adds: In this section are some of the most beautiful places of the continent, and the climate is delightful at all times. It never gets really cold nor does it have extreme heat. Nature has been kind to this section in all respects, and the people have responded.

Ride Along With Us!

We continue eastward from Washington State into Idaho, beginning with YTA Idaho Mile Marker 000.0 assigned to the starting point at the Washington-Idaho state line.

TRAVEL ALERT: Check Current Road Conditions at Idaho DOT.

Some roads mentioned below are Closed / Restricted during Winter Months.

Click here for Idaho Trail Tales

Welcome to the Idaho Yellowstone Trail Travel Guide

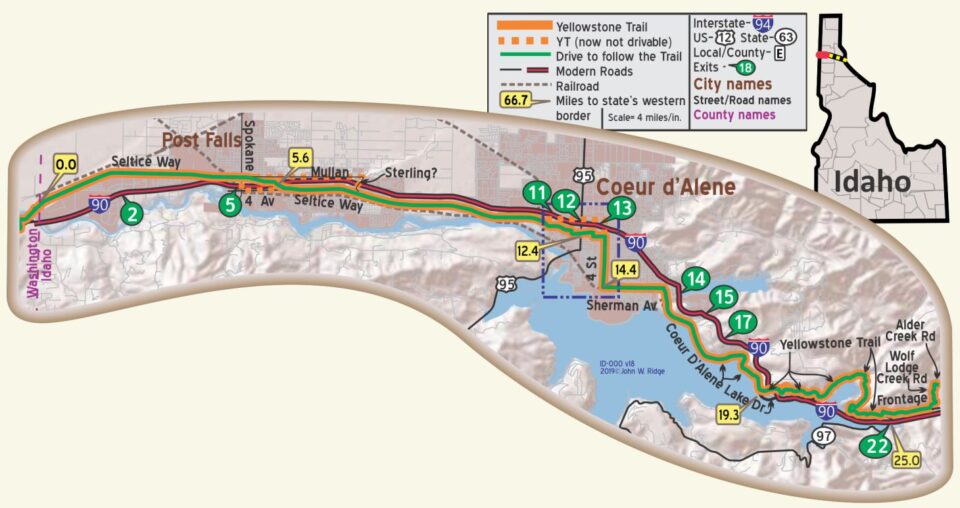

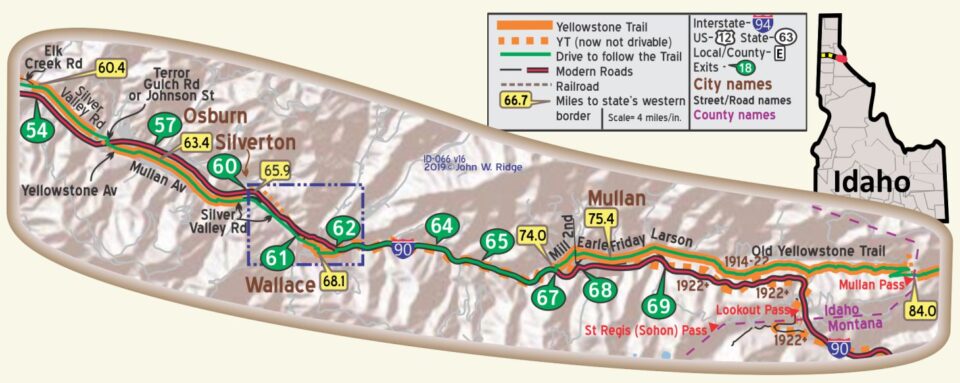

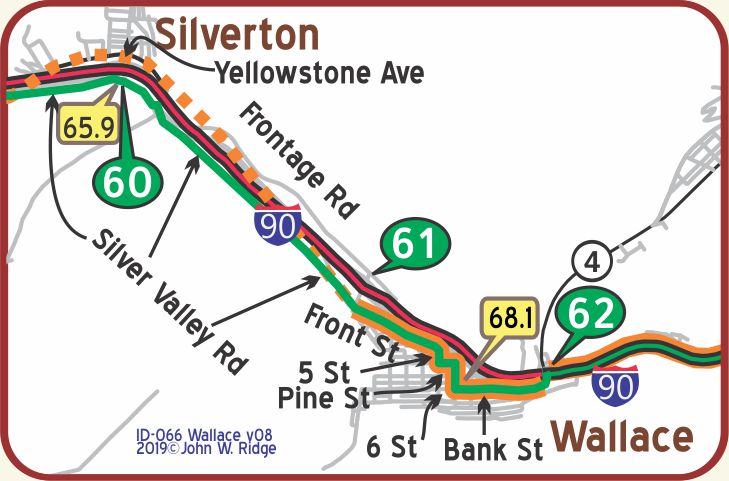

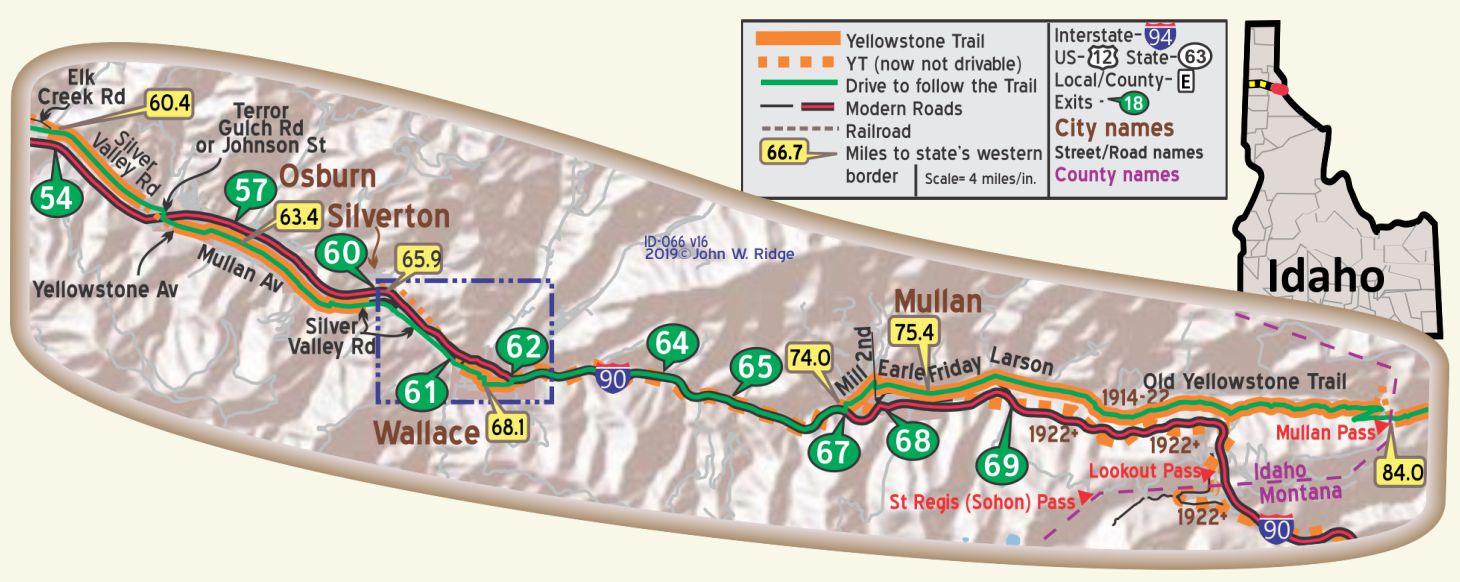

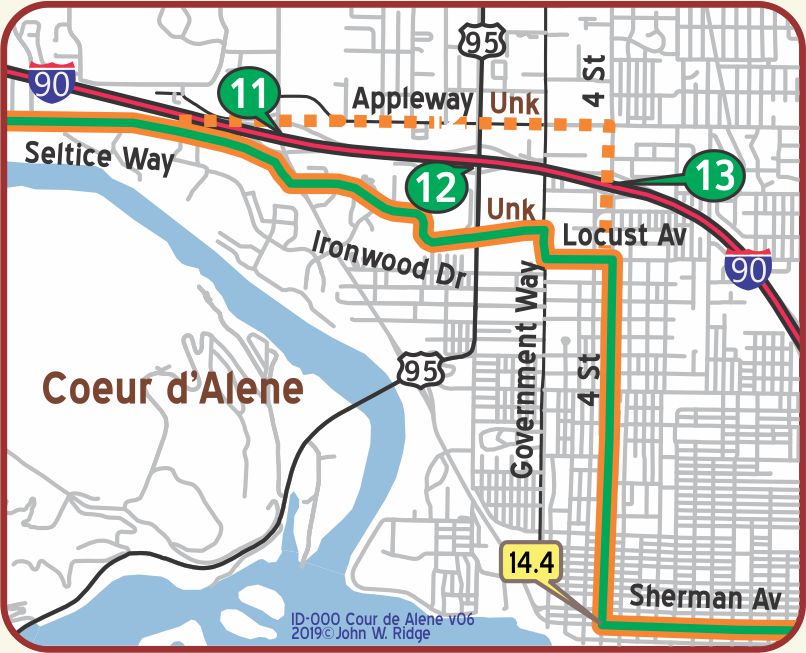

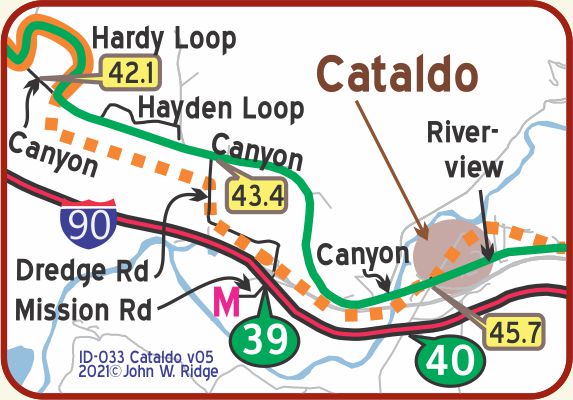

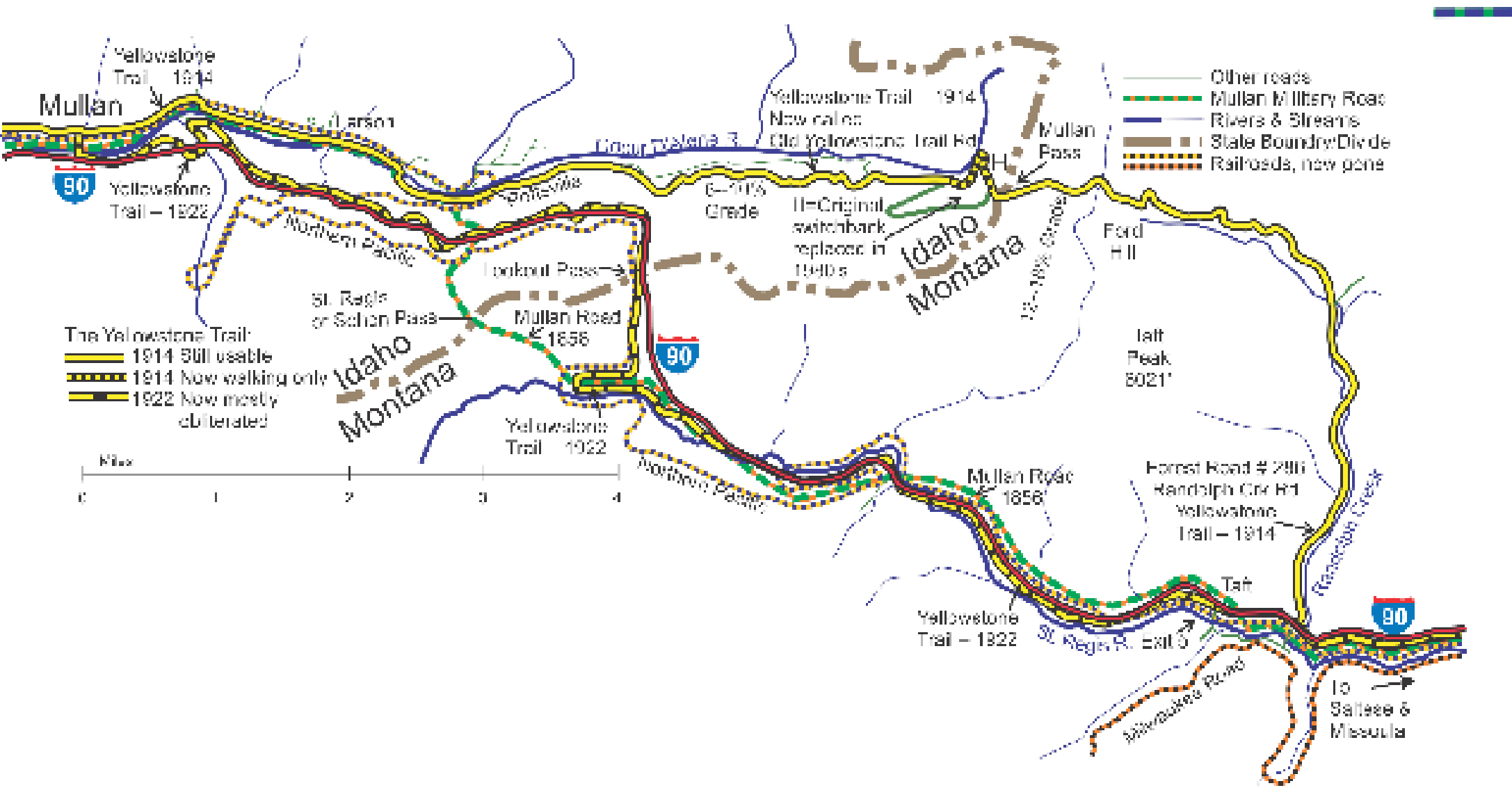

The one-of-a-kind custom maps provided were created by John and Alice Ridge during their multi-decades long research of the YT.

Each map has a legend showing a variety of map items allowing you to closely follow the YT.

Follow the map’s green line “—————” to Drive the Trail.

The map’s green circle markers

The map’s green circle markers

are modern highway exit numbers

used for current location reference.

The map’s yellow rectangle mile markers show path of YT and distance to state’s west border. Click the corresponding number in text for directions and more information.

The map’s yellow rectangle mile markers show path of YT and distance to state’s west border. Click the corresponding number in text for directions and more information.

For Directions, click the Idaho State (ID-) YTA Mile Marker Numbers below linking you to a real-time map.

ID-000.0 Washington/Idaho Line

ID-005.6 Post Falls

(2,147 alt. ; 509 pop.) is a small lumbering and fruit-packing town on the Spokane River.

A half mile south of it is the Post Falls Dam, which impounds the river and delivers power to the eastern part of the Inland Empire. WPA-ID*

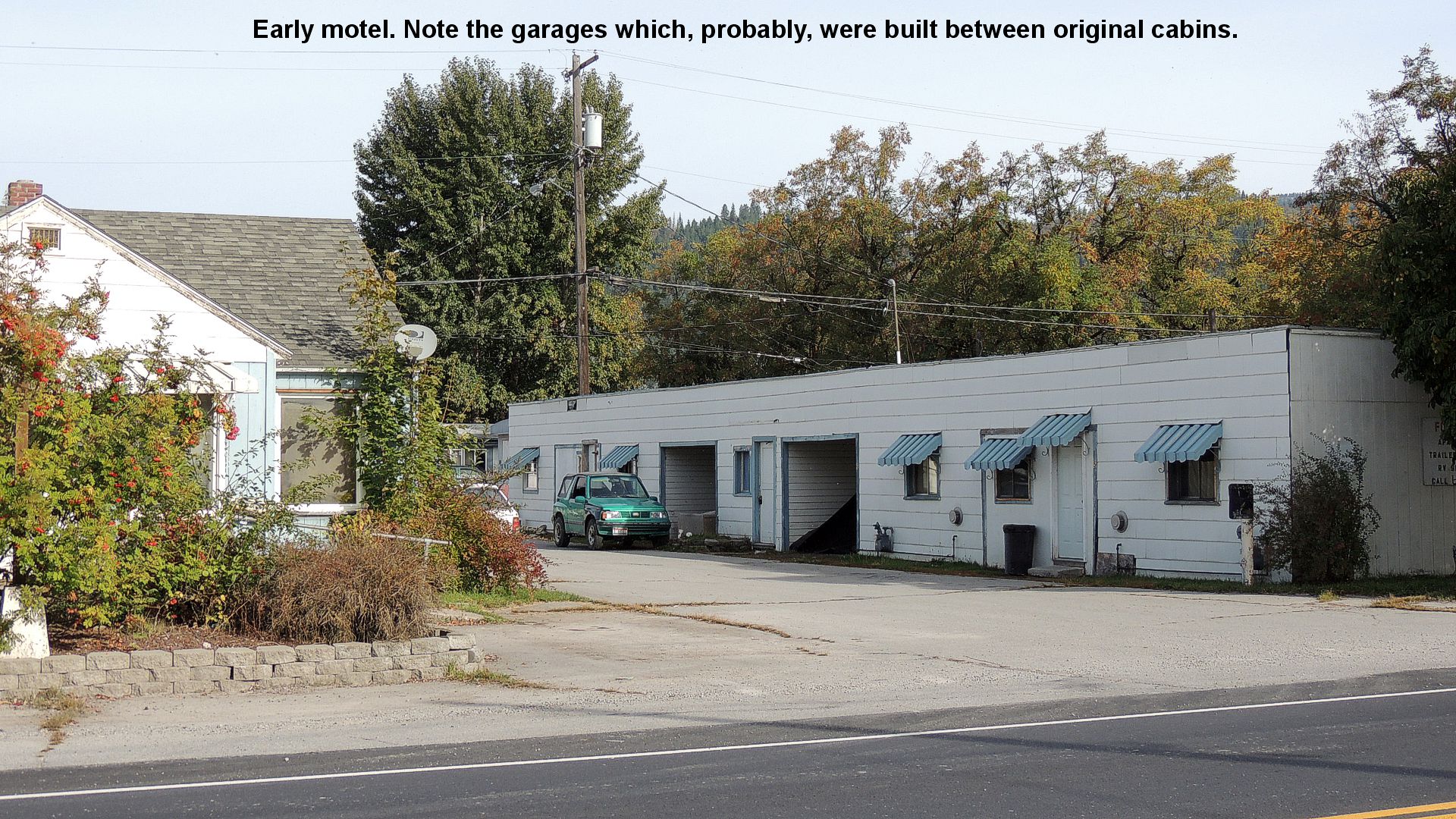

A farm and saw mill town. Reynolds Garage leads. Free and pay camp. Kamp Komfort, 9 clean cottages, $1; camp 50c. MH-1928*

101 E 4th Ave. (Yellowstone Trail). Post Falls Historical Society. Located in a small 1923 building. Local artifacts and special displays are featured.

101 E 4th Ave. (Yellowstone Trail). Post Falls Historical Society. Located in a small 1923 building. Local artifacts and special displays are featured.

316 E 5th Ave. Vintage Guitars. We mention this only because there is a 1917 Gibson “harp” guitar there along with other antique guitars, some possibly recognized by Yellowstone Trail travelers 100 years ago. With luck, some current famous guitarist may be there when you stop.

705 N Compton St. near Seltice Way. Treaty Rock Park.

Treaty Rock Park is the site of the legendary treaty between Chief Seltice of the Coeur d’ Alene and Fredrick Post, the town’s founder. It features a section of the rock with the words “June 1, 1871, Frederick Post,” along with Native American pictographs. The historic petroglyphs and pictographs (by tradition, created 1871), located in the city park, are listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

NOTE: From ID-0.0 to ID-5.6, the 1919 Idaho Dept. of Agriculture/Univ. of Idaho Soil Map suggests the YT followed the old Mullan Road which is now Seltice Way. The 1915 Westgard map shows, from the west, the YT following the Seltice Way, Spokane St., 4th Ave. then joining Seltice Way going east.

Within northern Coeur d’Alene, the route shown on the city map between Seltice Way and 4th St. is, at best, an approximation, although some travel on Government Way can be assumed.

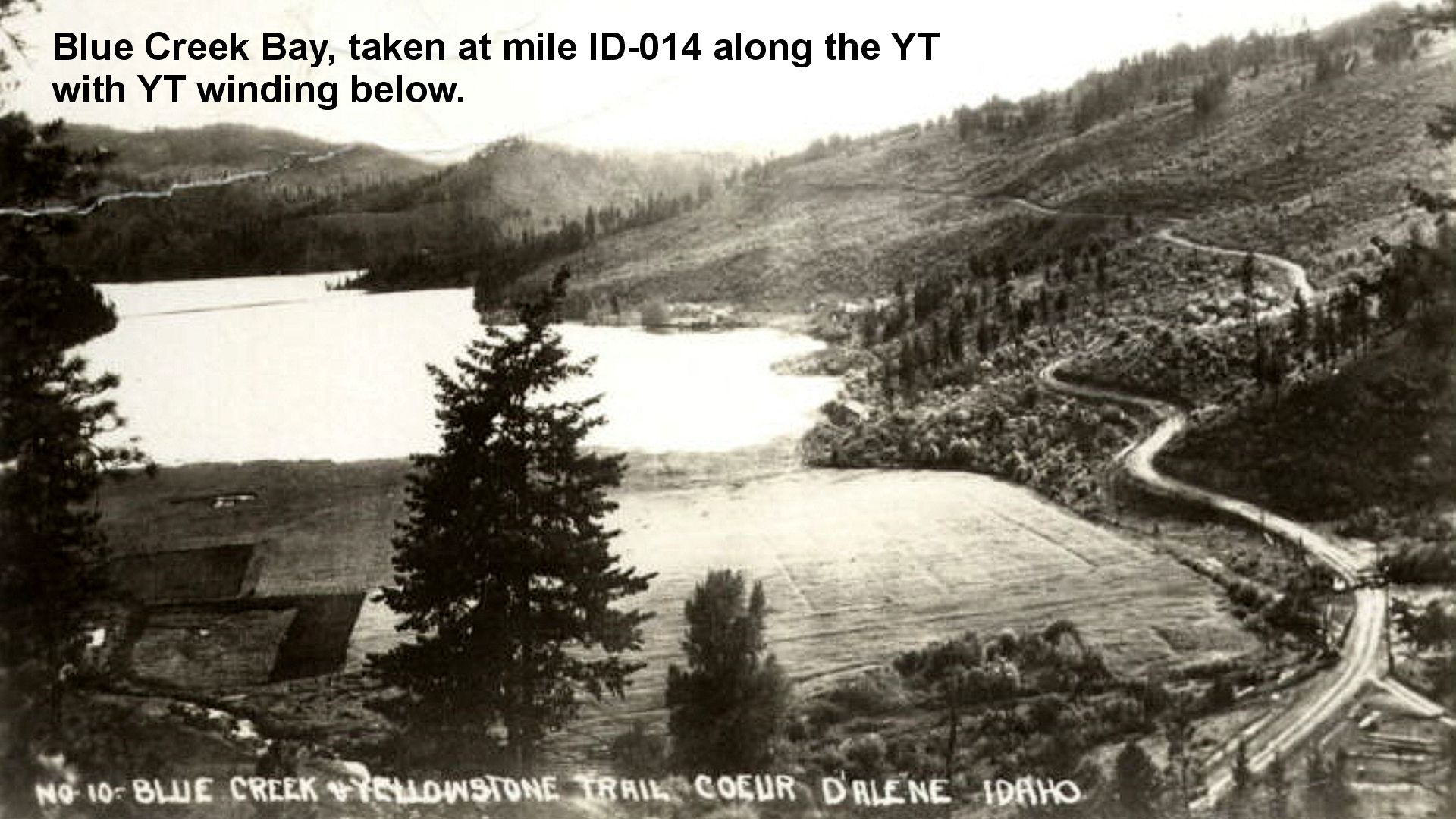

Interestingly, Westgard’s 1915 map puts the YT on the east side of Coeur d’ Alene along the present inland Sunnyside Road from Bennett Bay to Blue Creek Bay and improbably continues east directly to Alder Creek Road. Further research found that that route was the original Mullan Military Road route. Either it was travelable by auto when Westgard visited or, more likely, Westgard simply reported that route without driving it.

ID-014.4 Coeur d’Alene

ID-014.4 Coeur d’Alene

On account of its beautiful location at the base of the Coeur d’Alene mountain range, a part of the great Rocky divide, the adjoining lake and its picturesque setting, its steamboat lines and railroad facilities, the city has become known as a summer resort, and is visited by thousands yearly. The great transcontinental highway, adopted by the Yellowstone trail and the National Parks highway, passes through the city, and automobile tourists stop over to enjoy the commodious camping grounds and other recreations, as they speed across the country. BB-1921*

COEUR D’ALENE at Powell’s Store. Pop. 11,000. Is a noted lumber center. A pleasant trip is to Hayden Lake, about seven miles, where boating, fishing and golf may be enjoyed. Silver Grill is best; lunch 40c. City Camp 50¢, is in town in a fine grove, but not very level. MH-1928*

DESSERT HOTEL is best. Nearly all outside rooms. Well kept. Sgl. $1.50-$2.50; dbl. $2, bath $3-$3.50.

KOOTENAI MOTOR CO. leads; has machine shop, open at all times. Labor $1.50. Ph. 400, for service car.

SIMPSON MOTORS, Ford, a modern agency. Ph. 532.

COEUR D’ALENE TIRE SHOP, 4th St. on Trail, is finely fitted for service. Ph. 479J. MH-1928*

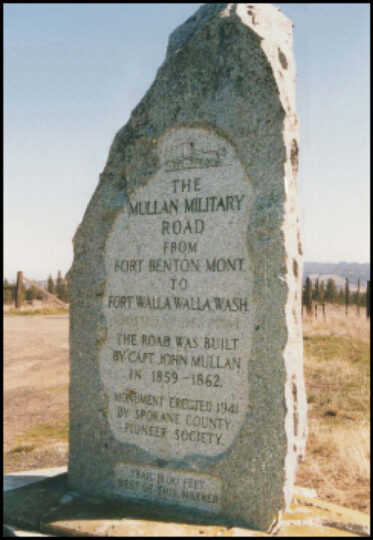

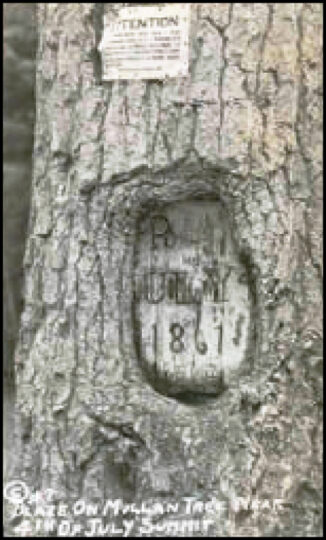

115 Northwest Blvd. Museum of North Idaho. Exhibit topics include the Mullan Road, Fort Sherman, early transportation, logging and mining. The remains of “The Mullan Tree” are there. July 4th, 1861, found Captain John Mullan and his military detachment in what is now called 4th of July Canyon between Coeur d’Alene and the Cataldo Mission. Mullan was constructing a military road from Walla Walla, Washington, to Fort Benton, Montana. On that day Mullan carved M. R. into a tree to mark it as being on the military road. That carving remained on the tree until 1962 when the tree blew down. The carving is now here. See Trail Tale: Mullan Road.

See also at the museum the story of the Flyer, a steam boat that provided freight service on the lake and up the St. Joe and St. Maries Rivers. On weekends it doubled as a pleasure boat, popular with the college students. It was important to the growth of Coeur d’Alene from 1909-1939, when the Yellowstone Trail coursed through town.

NOTE: At ID-19.3, in modern times, when traveling from the west on Coeur d’Alene Lake Rd., the intersection with the YT is poorly marked and easy to miss.

NOTE: ID-028.0 to ID-033.3 – The frustrations of research:

The 1919 map issued by the Idaho Dept. of Ag. Soil Map is a detailed but poor map for this stretch.

Either the surveying was poor, or the map drawing was crude.

Close, but not a good match for the terrain.

But, the label “Yellowstone Trail” demonstrated the acceptance and common use of that name.

¦

ID-033.3 at Exit 28, Summit of 4th of July Pass

Fourth of July Summit, el. 3,163 ft.; good rooms at Hawley’s Tavern; lunch, phone and supplies; cabins, $1.

Uncle Sam’s spring; pure water. WPA-ID*

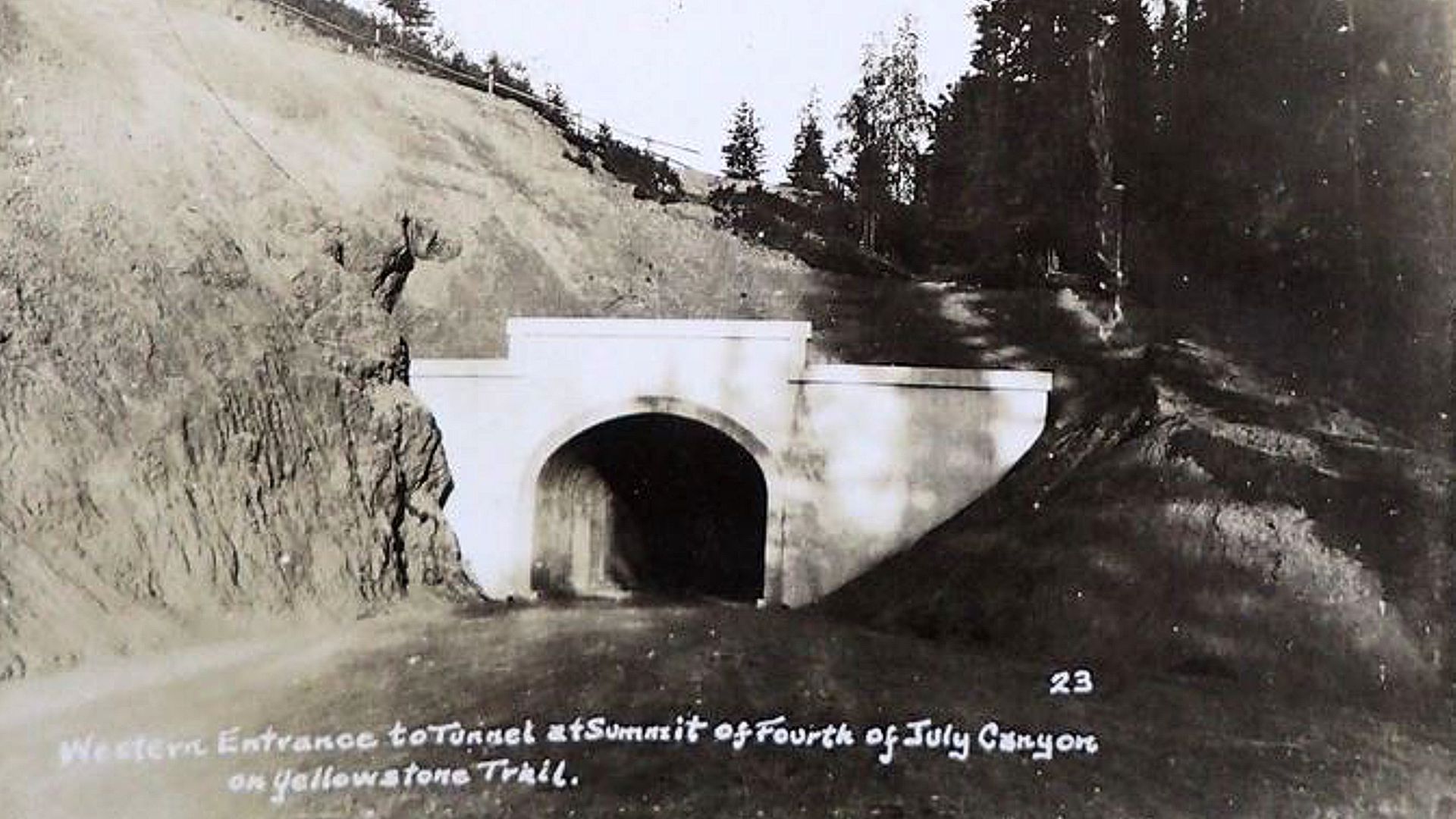

The FOURTH OF JULY SUMMIT (3,290 alt.) is marked by a tunnel 394 feet in length. WPA-ID*

[Built after the YTA ended in 1930.]

Northeast from the summit on a dirt road is the MULLAN TREE.

Northeast from the summit on a dirt road is the MULLAN TREE.

Standing in the center of a fifty-acre park, this tree still bears the date, 1861, and the initials M. R. (Mullan Road) [Actually, “Military Road”].

It was here on July 4, 1861, that Captain Mullan and his men were encamped while building the Mullan Road.

They raised an American flag to the top of the tallest white pine, and from this circumstance the canyon has taken its name. WPA-ID*

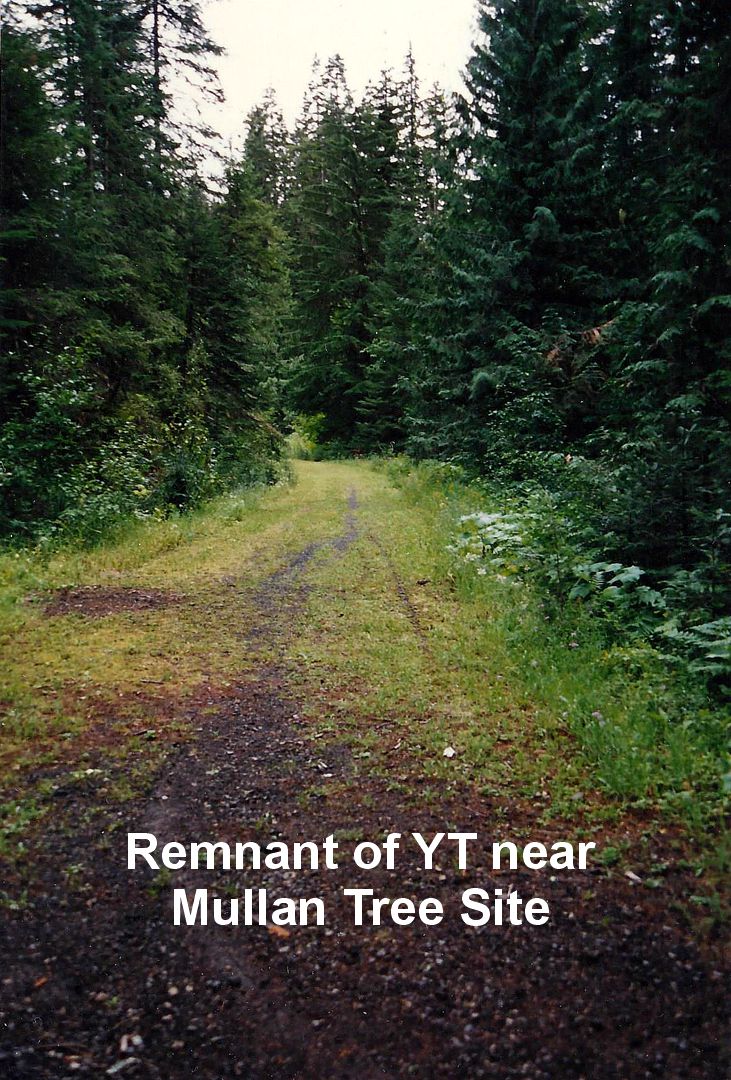

One mile east of I-90 Exit 28 at the Summit is the most pleasant Mullan Tree Monument rest stop where the tree once stood. Today the Mullan tree carving is preserved at the North Idaho Museum, Coeur d’ Alene, but there is a little piece of old US 10/ Yellowstone Trail to contemplate. The sign at the monument says, “The first road built over this pass in 1861 followed the creek bed”.

In 1916 this first “road” was replaced by US Highway 10 [sic] on which you are now standing.

In 1916 this first “road” was replaced by US Highway 10 [sic] on which you are now standing.

A goal for old-timers nursing their early cars up this steep grade was a rest stop at the top containing a store with a dancing bear to attract tourists.

A 473 foot long tunnel was built under the pass in 1932 to reduce the steep grade. In 1958, Interstate 90 replaced US 10 and bypassed the tunnel. Reconstruction of I-90 in 1988-89 resulted in the removal of the old tunnel.”

NOTE: ID-037.1 to ID-039.0 Canyon Rd. is probably the YT but it is closed at the west end at the road maintenance shop.

NOTE: ID-037.1 to ID-039.0 Canyon Rd. is probably the YT but it is closed at the west end at the road maintenance shop.

ID-039.0 4th of July Canyon

CANYON GARAGE, small but good; has wrecker. MH-1928*

Huckleberries can be found from Coeur d’Alene forests through the Silver Valley to Wallace and into western Montana from June through September. They look just like blueberries to us Easterners. Buy a huckleberry shake or sundae or pancakes or martini or anything huckleberry in the area. The shakes are absolutely yummy.

NOTE: Near ID-043.0, the YT may have followed Canyon Road and may have used Hayden Loop for some years. The route of the Trail in Cataldo and for several miles west is not clear because of repeated realignments and improvements.

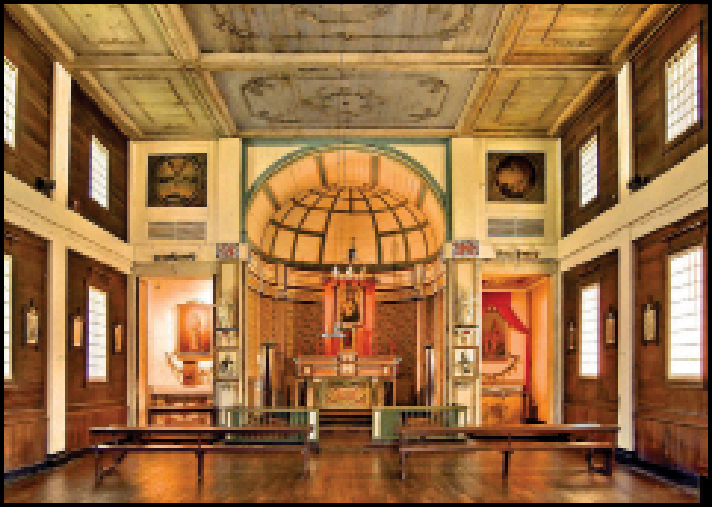

WAYSIDE: ID-44.5 Old Mission State Park

WAYSIDE: ID-44.5 Old Mission State Park

This is an interesting historical short side-trip.

I-90 was built on top of the Yellowstone Trail in much of this area.

If you are on I-90 take Exit 39 to see the Old Mission.

If you are on the driveable Yellowstone Trail turn south on Dredge Rd., and continue on Mission Rd.

This beautiful white building, standing on a low mound, was built in 1848 by Father Antonio Ravalli. (photo right)

Also known as the Mission of the Sacred Heart or Cataldo Mission, this National Historic Landmark has a fascinating history. It is the oldest standing building in Idaho, constructed with no nails by Fr. Ravalli and members of the Coeur d’Alene tribe. For more about the Old Mission, see Trail Tale: Cataldo.

ID-045.6 Cataldo

ID-045.6 Cataldo

The town was originally named Old Mission. A steel bridge over the Coeur d’Alene River was built in 1919.

April 12, 1919 Western Highways Builder

The road used by the Yellowstone Trail between Cataldo and Kingston was originally built in 1924/1925 and rebuilt by 1938 because it was “narrow, crooked, and unable to withstand present traffic and heavy loads.”

1938 Annual Report of the Idaho Transportation Dept,

Jeff Stratten

Note: What was used before 1924?

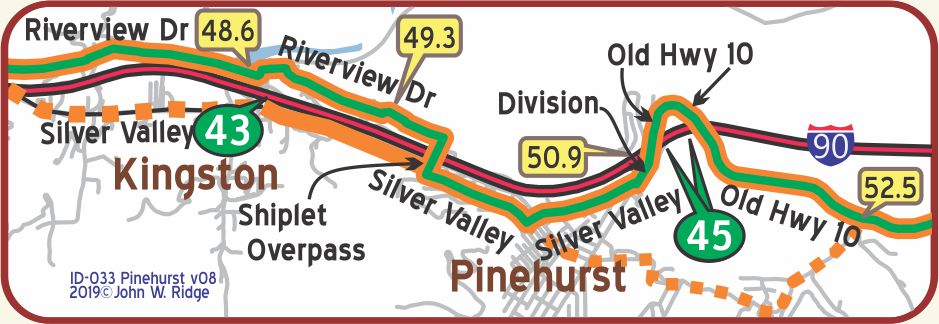

ID-048.6 Kingston

ID-048.6 Kingston

At ID-49.3 the Yellowstone Trail apparently followed

Doolittle Rd. running north of Riverview for 7-800 feet.

The construction of I-90 relocated the original run just to the east of here, requiring using the overpass today.

WAYSIDE: The Snake Pit 1480 Coeur d’Alene River Rd. Enaville Resort (AKA Snake Pit) at Enaville a mile or two north of Kingston. If you are on the Yellowstone Trail (Riverview Drive), turn north onto Coeur d’Alene River Road for one mile. If on I-90, take Exit 43 toward Kingston. Turn left onto Coeur d’Alene River Road and travel one mile. The Snake Pit is on your right. Who knows why it is called the Snake Pit, but, in spite of its wildly eclectic interior, there is good food there. Ever had Rocky Mountain oysters? We were last there several years ago so things may have changed, but we include it here because it has been a staple of the area since 1880 and is near the Trail. Chances are Trail travelers stopped there.

ID-050.8 Pinehurst

The Coeur d’Alene Mountains flanks, late in every summer, are blue with ripe huckleberries. WPA-ID*

ID-053.8 Smelterville

ID-053.8 Smelterville

The name was chosen by the citizens because of the large smelter of the Bunker Hill mine established there.

West of Kellogg with its miracles of machinery, there is still to be seen a poisoned and dead or dying landscape. Trees slain by the invisible giant still stand with lifeless limbs and with roots still sucking the poisoned earth. WPA-ID*

NOTE: At Smelterville, between, roughly, ID-54 and ID-56, the YT followed a twisty road south of McKinley (Old US 10) through the Bunker Hill Superfund site.

ID-056.7 Kellogg

(2,305 alt. ; 4,124 pop.) Kellogg is a famous mining spot, with the Bunker Hill and Sullivan, the largest lead mine in the United States, located here. Above it the denuded mountains declare the potency of lead. The Sullivan Mine here has a development of sixty-four and a half miles and (with 560 men) the largest payroll of any mine in the State. WPA-ID*

Home to a major smelter, Kellogg was battered in the early 1980s when the smelter shut down and became an EPA Superfund site. Before that, the citizens had turned to Silver Mountain and tourism as a saving grace.

To move skiers from Kellogg to the mountain top, they built the world’s longest single-stage gondola.

The mountain offers 50 runs, 1,500 acres, and a 2,200 vertical foot drop.

Silver Mountain Gondola ride ticket office is at 610 Bunker Ave. We mention this obviously post-Yellowstone Trail entertainment because as you drive through town you cannot help but note the gondola as it whisks right over McKinley Ave. (Yellowstone Trail) on its way up the mountain. The gondola also symbolizes the “new” Kellogg, like a phoenix rising from the dregs of poisoned soil to affluent condos.

300 E Cameron Ave. (Yellowstone Trail). Miners Hat Realty Building, a doff of the “hat” to the history of the town.

Corner of W Cameron Ave. and S Division St. The former site of the Yellowstone Trail Garage in the 1920s (see photos right and below).

Corner of W Cameron Ave. and S Division St. The former site of the Yellowstone Trail Garage in the 1920s (see photos right and below).

Today this spot is home to the ubiquitous Dave Smith Motors, a multi-state retail auto sales company.

Albert Wellman owned The Yellowstone Trail Garage, selling Dodge and Plymouth products. The gas pumps faced Cameron Ave., “which was the highway,” according to Roads Less Traveled by Dorothy Dahlgren and Simone Kincaid of North Idaho Museum (North Idaho Museum Press, 2007).

820 McKinley Ave. The Staff House Museum. Otherwise known as Shoshone County Mining and Smelting Museum. The name comes from the former purpose of the house: to house resident and visiting managers of the Bunker Hill & Sullivan Mining Company.

820 McKinley Ave. The Staff House Museum. Otherwise known as Shoshone County Mining and Smelting Museum. The name comes from the former purpose of the house: to house resident and visiting managers of the Bunker Hill & Sullivan Mining Company.

Displays are mainly about mining, and the Bunker Hill Mine in particular, plus an art gallery.

210 Main St. McConnell Hotel had an early radio broadcast antenna on the roof for radio station KWAL. If you had one of the early auto radios you might have heard out of the ether “WKAL broadcasting to you from the roof of the McConnell Hotel,” wrote Dave Habura in the Yellowstone Trail Association newsletter, the Arrow, August 2011. The building now is vacant.***

***UPDATE*** The McConnell Hotel was gutted during a fire in 2017, and was completely destroyed. The lot sits empty today.

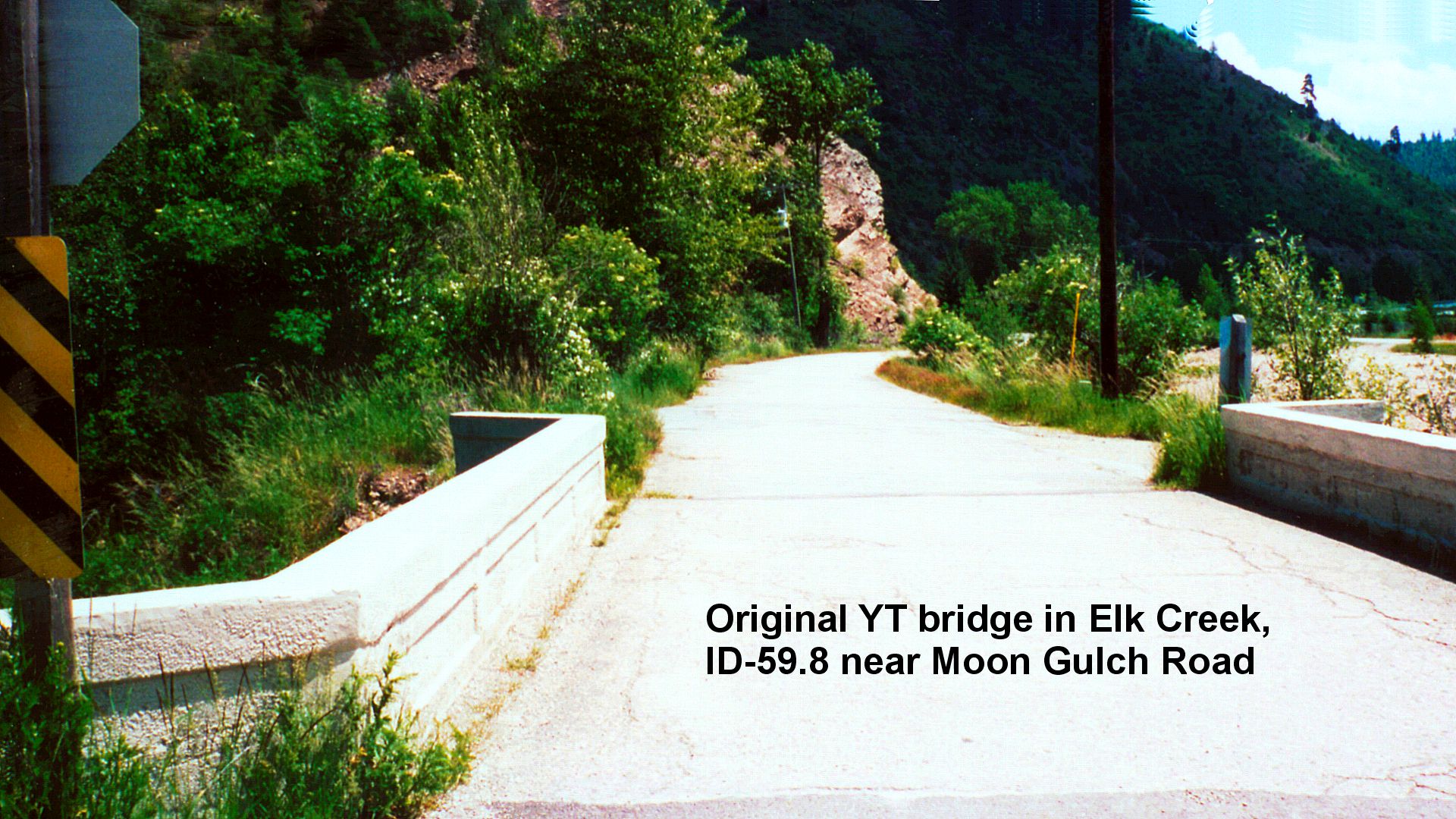

NOTE: Between ID-059.1 and ID-060.4, the driving line follows Silver Valley Rd. (“Feeder” or “Frontage” often appended to the name), but the original YT followed Elk Creek Rd., now only partially driveable parallel on the north of Silver Valley Rd. Access can be had at ID-59.7 at Moon Gulch Rd.

NOTE: Between ID-059.1 and ID-060.4, the driving line follows Silver Valley Rd. (“Feeder” or “Frontage” often appended to the name), but the original YT followed Elk Creek Rd., now only partially driveable parallel on the north of Silver Valley Rd. Access can be had at ID-59.7 at Moon Gulch Rd.

Just several feet to the east of Moon Gulch Rd. on Elk Creek Rd. is an old Yellowstone Trail bridge of interest. It might not be driveable, but the YT followed Elk Creek Rd. to the east to ID-060.4 near the Miners’ Memorial. Apparently, Elk Creek Rd. went further east behind the location of the Miners’ Memorial along a road, now lost, that emerges on to Elk Creek Rd. at ID-061.0.

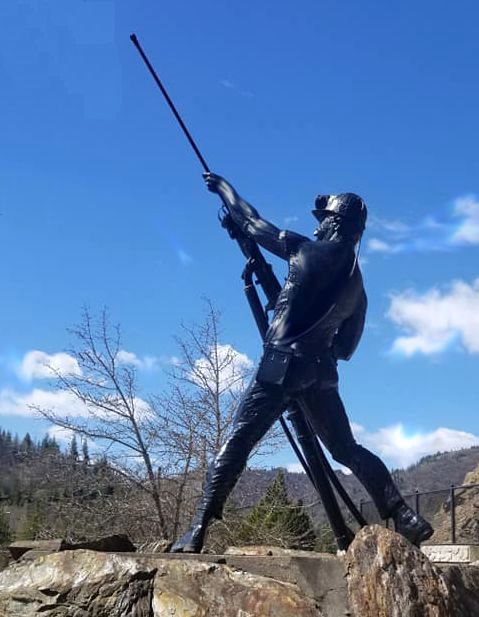

ID-060.4 Sunshine Miners Memorial

On Silver Valley Rd. on the Yellowstone Trail at I-90 Exit 54 is the Sunshine Miners Memorial, a statue which honors 91 fallen miners killed in a 1972 mine fire.

The strong miner is clutching a pneumatic rock drill and his head lamp stays lit all the time.

This is an important part of the history and culture of the area.

ID-063.4 Osburn

ID-063.4 Osburn

Through this canyon area are numerous streams, majestic forest scenery, and tall hills. To this day it is a beautiful area.

NOTE: It is believed that the YT ran on today’s Yellowstone Ave. near Osburn and crossed the Coeur d’Alene River just west of Terror Gulch road (ID-61.9), following Silver Valley Road to the west and Yellowstone Ave. to the east.

ID-068.1 Wallace

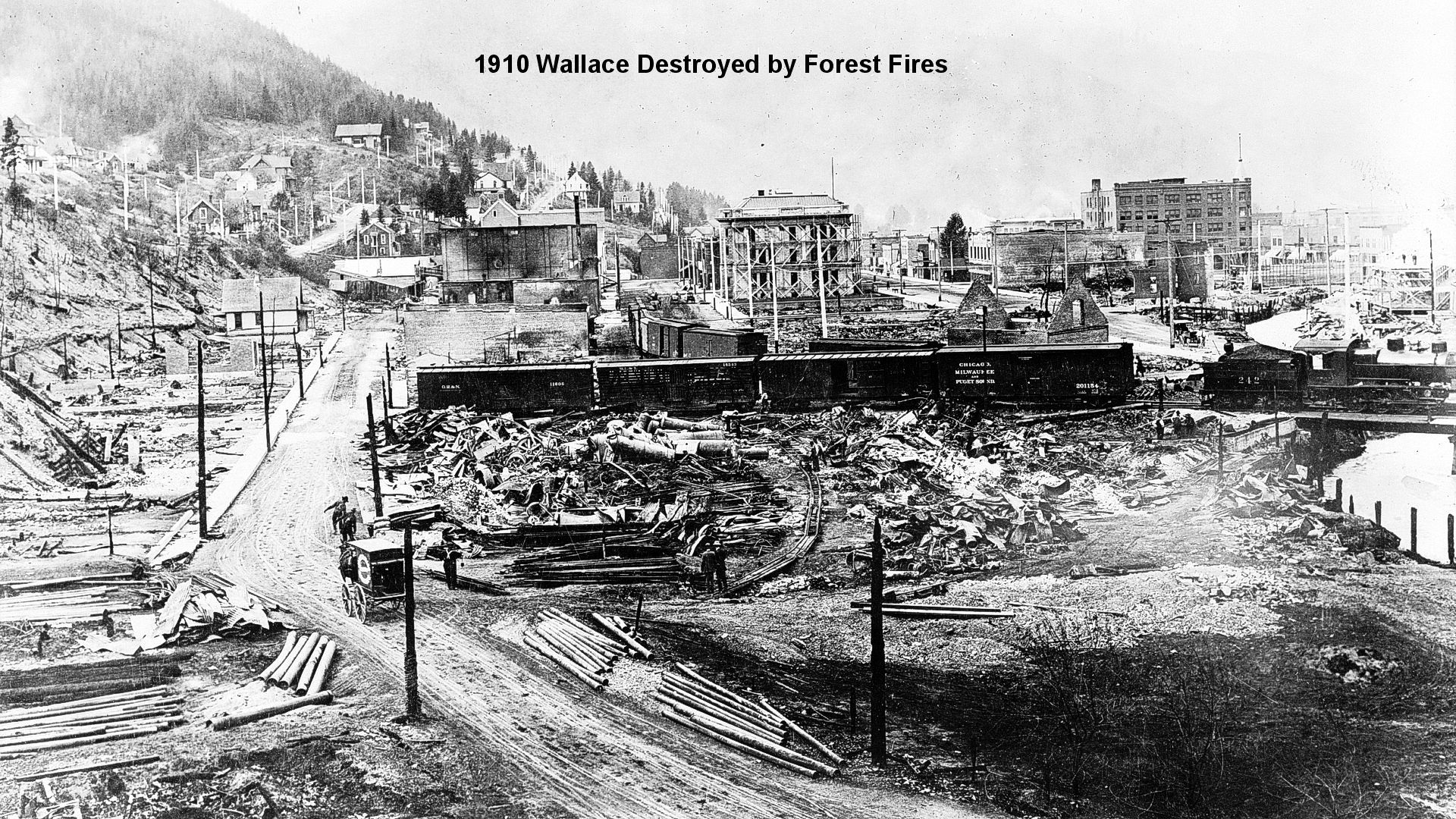

(2,728 alt.; 3,634 pop.), standing in a triangular valley in which many streams enter the main fork of the Coeur d’Alene River, is the seat of Shoshone County and the distributing center of this large mining and lumbering area. The great fire of 1910 partly destroyed this town, since rebuilt and quite picturesque, with its better homes terraced on the mountainside, row on row. In its lovely little park at the western end is another monument to Mullan. WPA-ID*

Since Wallace is jammed into a very narrow canyon, there isn’t much choice for a road. The Yellowstone Trail went right through town: Front St., 5th, Pine, 6th, Bank. There wasn’t much choice for I-90, either. The citizens nixed the idea of splitting the historic town in two, so you will see that the super highway went up and over the northeast side of town, with the Yellowstone Trail running beneath part of it. They used to advertise this town as “the last stop light,” referring to the last portion of I-90 which was built there in 1991, eliminating stop lights on that highway across the entire country. The site of that “last stoplight” was the corner of Bank and Seventh St. There is a stoplight still there today.

Since Wallace is jammed into a very narrow canyon, there isn’t much choice for a road. The Yellowstone Trail went right through town: Front St., 5th, Pine, 6th, Bank. There wasn’t much choice for I-90, either. The citizens nixed the idea of splitting the historic town in two, so you will see that the super highway went up and over the northeast side of town, with the Yellowstone Trail running beneath part of it. They used to advertise this town as “the last stop light,” referring to the last portion of I-90 which was built there in 1991, eliminating stop lights on that highway across the entire country. The site of that “last stoplight” was the corner of Bank and Seventh St. There is a stoplight still there today.

The entire town is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and whole blocks in the business district have remained virtually intact for 100 years or more. Note the sign at Bank and 6th St., noting “The Center of the Universe.”

509 Bank St. The Wallace District Mining Museum is a treasure trove of information about mining and miners’ lives with historic photos and artifacts. It also has pictures of two Hollywood movies filmed in Wallace, “Dante’s Peak” in 1997 and “Heaven’s Gate” in 1979. The “last stoplight” itself, “Old Blinky,” referred to above, is there.

509 Bank St. The Wallace District Mining Museum is a treasure trove of information about mining and miners’ lives with historic photos and artifacts. It also has pictures of two Hollywood movies filmed in Wallace, “Dante’s Peak” in 1997 and “Heaven’s Gate” in 1979. The “last stoplight” itself, “Old Blinky,” referred to above, is there.

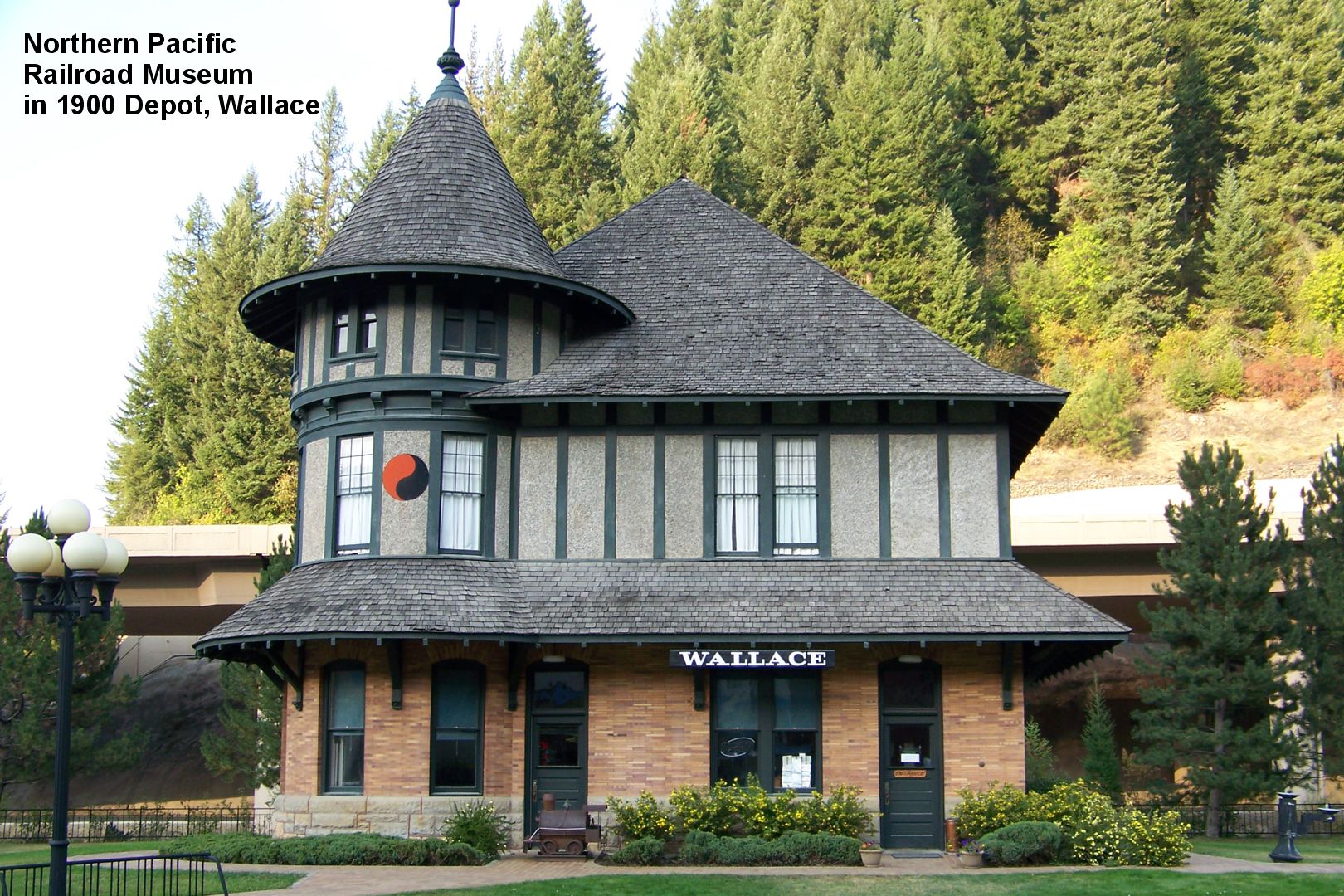

6th and Pine Sts. Northern Pacific Railroad Museum. This was the hub of the community with freight and passenger trains to Missoula running regularly. Robert Dunsmore, in Historic Wallace Idaho booklet says that, additionally, the mining community had three passenger runs daily until 1926.

There is a ton of data about the Northern Pacific Railroad in the West and its role in the Coeur d’Alene mining district in this recreated 1900 station. Spend time looking at the outside of this chateau-style beautiful building. Don Root, in Idaho Handbook (Moon Pubs. 1997) says that “this depot was carefully moved 200 feet to this location in 1986 after the new interstate threatened to run right over it.”

There is a ton of data about the Northern Pacific Railroad in the West and its role in the Coeur d’Alene mining district in this recreated 1900 station. Spend time looking at the outside of this chateau-style beautiful building. Don Root, in Idaho Handbook (Moon Pubs. 1997) says that “this depot was carefully moved 200 feet to this location in 1986 after the new interstate threatened to run right over it.”

609 Bank St. White Bender Building, home to the Silver Capital Arts and Mineral Museum; it showcases displays of minerals from the Silver Valley and other mining regions of Idaho and the West.

605 Cedar St. Oasis Rooms Bordello Museum. It was opened in 1895 and run as an active bordello until 1988, in spite of being outlawed 15 years previously. The rooms are preserved as they were when last used. We include it here because it is part of the history of the Yellowstone Trail era, is the only one we know of along the Trail, and may even have been visited by Trail travelers.

Pretty much all of the downtown of Wallace burned in the “Big Burn” forest fire of 1910. See more photos below of the Wallace 1910 Fire.

Pretty much all of the downtown of Wallace burned in the “Big Burn” forest fire of 1910. See more photos below of the Wallace 1910 Fire.

Ed Pulaski led 45 miners to a mining tunnel and saved the lives of 40 of them.

Tourists may visit that tunnel and a memorial sign one mile south of Wallace on King (Moon Pass Rd.).

Park and see the sign commemorating the 1910 fire and Pulaski,

then hike 2 miles to the tunnel.

Two newer monuments were unveiled in August, 2010, the 100th anniversary of the fire.

One is on the west side of town at the Visitor Center at 10 River St.

The second one is in Miners Union Cemetery on 9 Mile Cemetery Road.

NOTE: The Miner’s Union Cemetery is on 9 Mile Cemetery Road where you find a sign.

Pulaski later invented a fire-fighting axe with a pick on one end of the head and an axe on the other.

It is called the “Pulaski Axe” and is still widely used today in firefighting.

The Yellowstone Trail Garage in Wallace had two (2) different locations:

The earlier location was at 425 Pine Street. That building later was the home to Vester Eye Clinic, but is now empty (photos below).

The later location of the YT Garage was at 717 Bank Street. That building is now the Shoshone County Jail (photos below).

More Wallace Photos:

(some fire photos courtesy Shoshone News Press)

More Wallace photos:

ID-074.8 Mullan

ID-074.8 Mullan

Founded in 1884 between two silver-lead mines and shaken by strikes, it has managed to avoid homelessness of miners that usually falls in towns in such regions. The Morning Mine, still operating here, is the third largest lead producer in the U.S. and sustains most of the population of the town. On the right is the monument to Captain Mullan. WPA-ID*

MULLAN, IDA. pop 2,600; an active mining town. Bilberg Hotel has some modern rooms. Mullan Garage is best, has wrecker. Camp 50c, on level land at ball grounds. Fine water at the Bitter Root Spring. MH-1928*

229 Earle St. Captain John Mullan Museum.

Established in the old Liberty Theater, this museum illustrates the history of Mullan with exhibits of historical furnishings, photographs, newspapers, and mining relics.

The museum features information on the building of the Mullan Road from 1859-1862 from Fort Benton, Montana, to Fort Walla Walla, Washington.

102 Hunter Ave. St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church. Built out of wood in 1888.

.

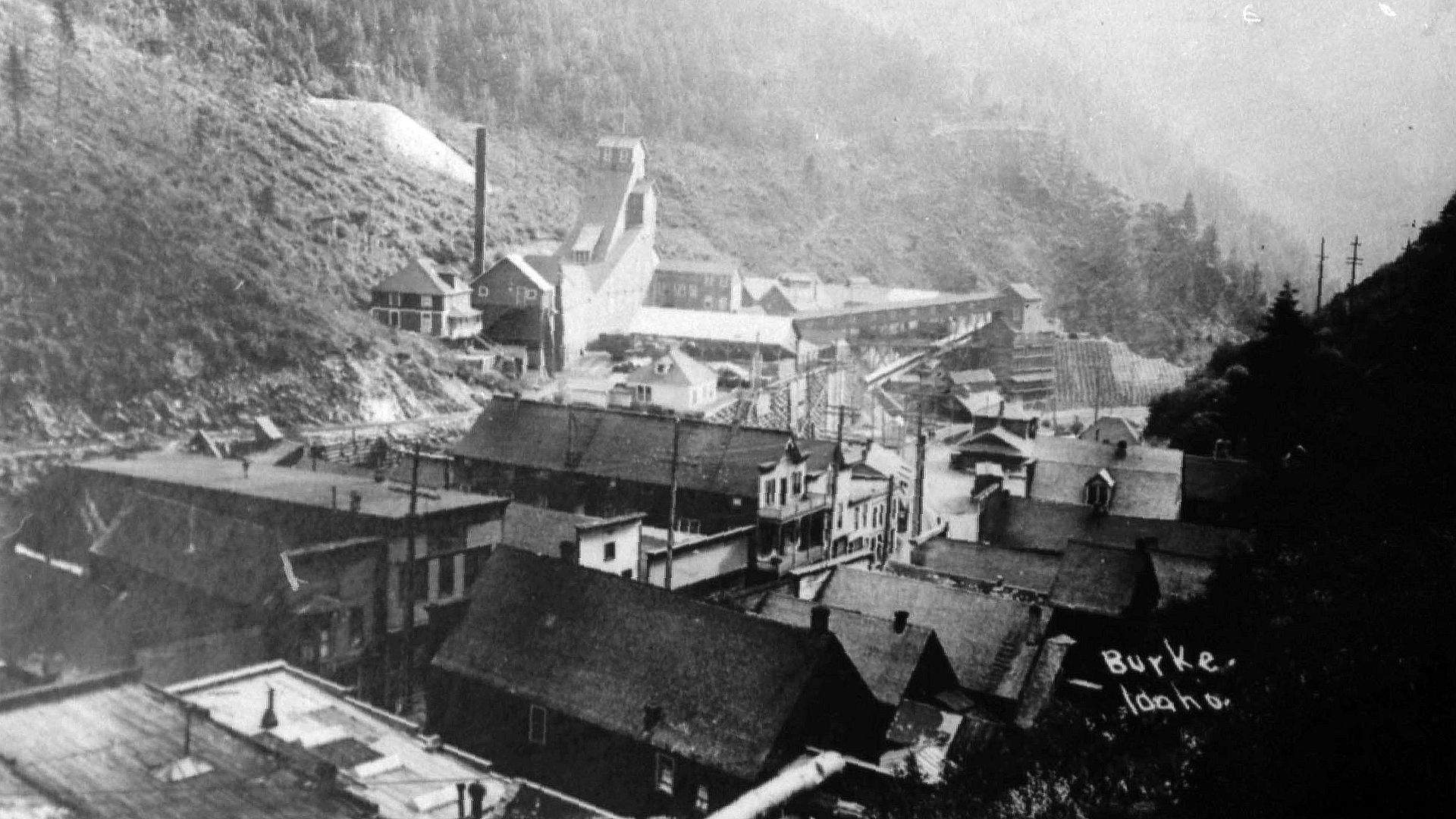

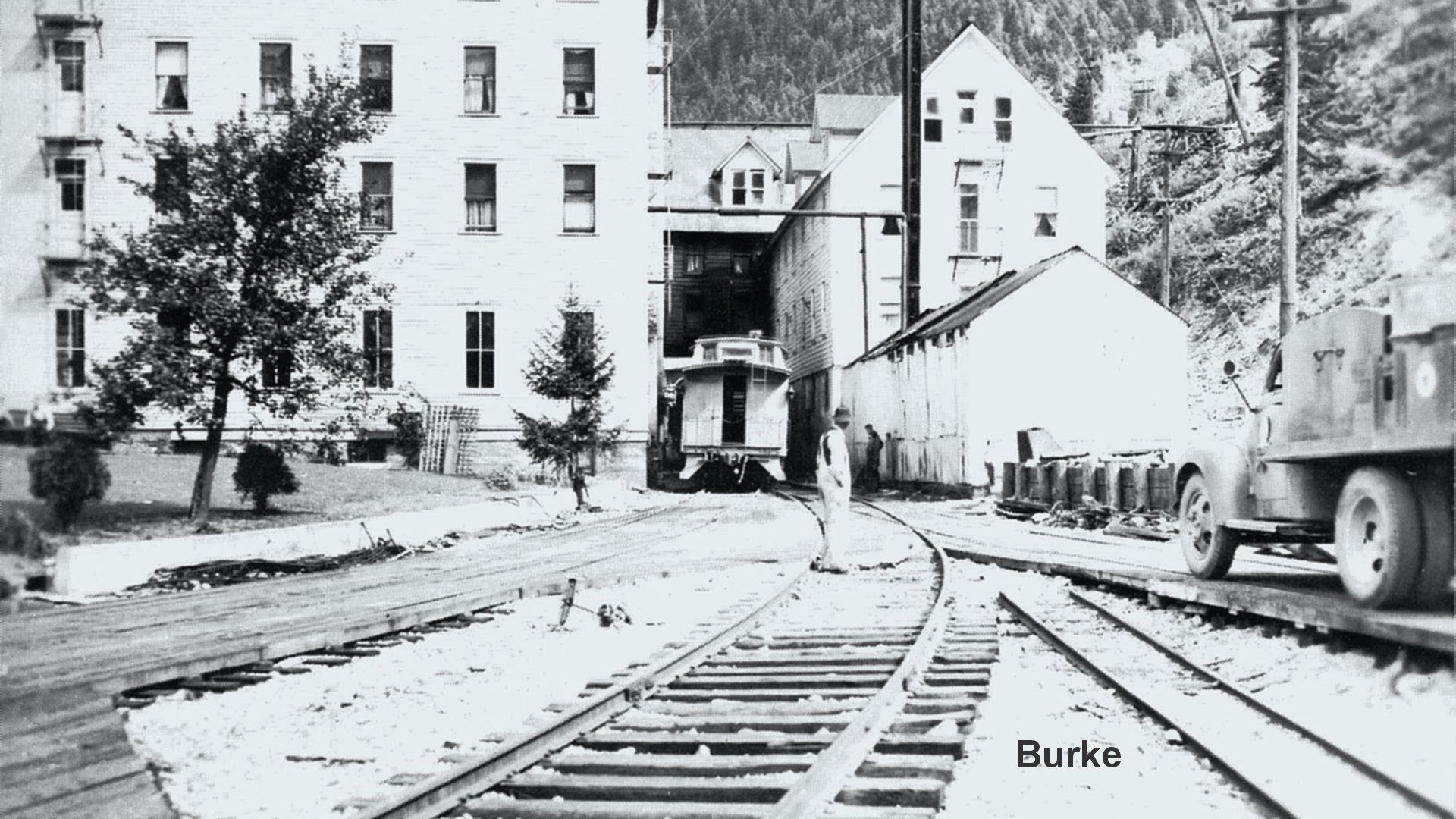

. WAYSIDE: Burke – You might be interested in driving to a former mining camp-turned-town-turned-ghost town.

WAYSIDE: Burke – You might be interested in driving to a former mining camp-turned-town-turned-ghost town.

Burke is about 6 1/2 miles northeast of Wallace on ID 4 at the east entrance of Wallace. On the way you can see relics of the past: the Canyon Silver mine, Blackbear mine, and the Standard-Mammouth mines. In Burke was the Hecla-Star mine. The amazing thing about Burke is that the narrow main street is actually a covered flume for a creek and is also the route of a railroad. It is said that when a train went by, merchants had to pull in their awnings. There is even the story of a single hotel built on both sides of the narrow street. It literally had a road, two railroad tracks, and a covered creek running through it. We walked it and can attest to the narrowness of it all. Unfortunately, now there is very little of the town left to see besides the narrow street. There are, however, large mine structures left and the visitor can see the signs of the engines of the economy that drove the Silver Valley. See picture.

Read more about the “Mullan Tree” (photos below) in Trail Tales.

ID-083.6 Idaho/Montana Line – Mullan Pass

ID-083.6 Idaho/Montana Line – Mullan Pass

Original Yellowstone Trail/Randolph Creek Road over misnamed Mullan Pass.

NOTE: Just to the west of the divide, the early YT across Mullan Pass followed a switchback to the north. Sometime in the 1980s that switchback was replaced by the current less-demanding switchback. The old switchback is closed with a Kelly Hump, a pile of rock and soil to deter traffic. The 1917 Forest Atlas confuses the route of the switchback, seeming to have it cross the “river” to the NW side. Strange.

Lookout Pass Summit of the Bitter Root Mts.; the Idaho-Montana Line. Telegraph and water only. MH-1928*

US 10 crosses the Idaho-Montana Line over Lookout Pass (4,738 alt.). From the summit is afforded a view of a large part of two National Forests, the St. Joe and the Coeur d’Alene. One can still see the scars which remain from one of the worst forest fires in history. This epic of devastation wrote its record in a flood of flame that lighted the sky for a hundred miles and in mountains of smoke that obscured the sun. WPA-ID*

In 1938, the newer YT over the Lookout Pass was “oiled 40 feet wide in Mullan and 20 feet wide to the Pass. This eliminated the last unpaved section on the Yellowstone Trail” (referencing only the Idaho part of the YT, no doubt).

1938 Annual Report of the Idaho Transportation Dept., Jeff Stratten.

The “SnoGo” snowblower was a very slow moving unit, nonetheless got the job done!

The “SnoGo” snowblower used a Climax Blue Streak six-cylinder gasoline engine developing 175 horsepower at 1,200 RPM. Through the use of an eight-speed gearbox, speed could be varied from 1/4 to 25 miles per hour. It was claimed to be capable of throwing snow 100 feet to the side.

A 1942 Douglas County, Washington, “SnoGo”

is shown in the video below:

(Courtesy of the Douglas County Museum).

STATE-by-STATE Index

Washington – Idaho – Montana – North Dakota – South Dakota – Minnesota – Wisconsin – Illinois – Indiana – Ohio – Pennsylvania – New York – Massachusetts

*Abbreviations found throughout the YTA website, including year, have the following meaning:

ABB or BB – American Blue Books, guides written before roads were numbered so contain detailed odometer mileage notations and directions such as “turn left at the red barn.”

MH – Mohawk- Hobbs Guide described road surfaces and services along the road.

WPA – Works Project Administration. This government agency put people to work and paid them during the Great Depression of the 1930s. Some were writers. This agency was similar to the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) whose workers built parks, worked in forests and did other outdoor constructive work.

TRAIL TALES

Stories related to the Trail or its history are called Trail Tales.

Come Ride with Us:

The Yellowstone Trail in the Bitterroots

We are headed west on I-90 from Missoula, gracefully winding, climbing, and descending as we approach the mountains of the Bitterroots. It is a glorious ride, our Jeep never pulling hard, our eyes Velcroed to the scenery. The area from Saltese, Montana, to Mullan, Idaho, near Lookout Pass is one of breathtaking forest beauty. We are on our way to again visit an original piece of the Yellowstone Trail. We turn off the Interstate at Exit 5 at a place called Taft, five miles east of the Montana/Idaho border. Taft, a busy, rough-and-tumble mining camp in 1911, is now reduced to nothing but that exit sign. We must go east for 3/4 mile to find Lolo National Forest Rd. #286, Randolph Creek Road, which was the Yellowstone Trail. We have begun our adventure into the past on the Trail which is still gravel, still pleasantly driveable.

Tall pine trees lean against steep mountain sides. The surrounding quiet is broken by streams gossiping loudly, moving from 6,000 feet down into “gulches”whose names reveal a landscape of colorful history. Logging and old mining roads branch off, cut into blue hillsides to cling to the contours of the land. Six miles and 100 years from I-90 we reach the summit. Almost immediately we see that a cutoff was built in the 1980s to avoid the old wicked switchback just west of the summit. Going down the west side we leave Montana’s Randolph Creek Road and continue on Idaho’s Yellowstone Trail Rd. Another nine scenic miles later we arrive at the mining town of Mullan. That distance can take hours, though, with stops to walk the old switchback, stare at the mountain views and imagine a 1914 touring car coming over the hill.

The summit bears the misnomer of Mullan Pass. Captain John Mullan, who carved a military wagon road from Fort Walla Walla, Washington, to Fort Benton, Montana, from 1858 to1862, never saw this pass. His road dropped directly south from Mullan through what is now called Sohon Pass and followed the St. Regis River. The 1956 USGS map only confounds the problem by mistakenly naming the Yellowstone Trail route the Mullan Rd. The short lived military wagon road carried many pioneers but it was soon reduced to a pack horse trail, almost indistinguishable from forest floor. The Northern Pacific Railroad came winding around Lookout Pass in 1883 and made long-distance wagon roads obsolete.

First Attempt: Randolph Creek Road

Good roads had not reached the Northwest, but the auto had. By train. And the only way the autoist could travel through the Bitterroots was to put his car on the Northern Pacific. As always, it was the autoist who pushed hardest for roads. In 1911, reportedly at the insistence of the Wallace (Idaho) Automobile Club, Montana’s Missoula County and Idaho’s Shoshone County officials met to discuss the feasibility of each building a road, meeting at the state line. The Randolph Creek road project would rest on county shoulders because state aid was unlikely.

For two and one half years they argued. Montana people argued that Wallace could draw all of the mine business if a road were built their way, and Wallace chastised Montana for foot-dragging. Then some cooperation was achieved and the Randolph Road/Yellowstone Trail Road was completed in late fall of 1913. Newspapers on both sides of the border lauded the work as an economic boon, allowing travel from Missoula to Coeur d’Alene and thus connecting the Northwest to the Midwest with an auto road.

The Yellowstone Trail Association had watched the progress of the Randolph Creek road with keen interest. With this road through the Bitterroots, the Yellowstone Trail Association could now boast a route complete from Chicago to Seattle. During 1914 the road was a de facto part of the route and by 1915 it was marked and included on Association maps.

Almost immediately, a major problem emerged with the route. Both the Association and the locals knew that it snowed a lot in the mountains, but 10 to15 feet of it still on the road in May? In1916, it was eight feet deep on June 10! The inhabitants developed the habit of forming shoveling brigades to open the road, even inviting tourists to help shovel. But to the Yellowstone Trail Association this was a weak link in the chain that threatened the whole of it. Admitting to the driving public that they had to put their cars on the Northern Pacific to cross the Bitterroots nine months out of the year was inconceivable in light of their advertising. A better route had to be found.

Come Ride with Us Again

This time we are driving east from Mullan, Idaho, to Saltese, Montana, via the Lookout Pass route of the Yellowstone Trail. The general route was developed first by the Northern Pacific, with wide variances from the summit due to elevation challenges, then developed by Shoshone and Mineral Counties, then US 10 after 1926, and now used by I-90. We begin on River Street in Mullan and head over to I-90 east. The original Trail “crossed the flats and Willow Creek” and followed a serpentine path up to Lookout Pass. I-90 follows a gently curving route right in the same place, obscuring the old Yellowstone Trail totally.

In the comfort of our air-conditioned Jeep, we cruise the five miles to the summit of Lookout Pass. Not a good place to find traces of the old highway. We can explore the route of the Trail south for a short bit to the St. Regis River, but we must return to I-90 because there is no through section of the old road.

The Permanent Route: Lookout Pass

The presence of the Interstate, while destroying most of the this route of the Yellowstone Trail, also serves to confirm the selection of the Lookout Pass as a better route for a cross-country highway. Actually, that was probably the conclusion of many locals as well, not long after the Yellowstone Trail/Randolph Creek route was opened. Wesley Everett, manager of the Amazon-Dixie Mining Company, summed up the problems with the Randolph Creek route in a letter to the Superior, Montana, Mineral Independent in June 1915. He vigorously protested against the distribution of county tax money on the Randolph Creek road when the real traffic of the mining and lumbering industries and the traveler should go over Lookout Pass. He asked, “Why was the present road turned from the main valley to the summit at 12% grade, where the snow lies two months longer at an elevation of 400 feet higher, where there is a dangerous switchback, and where the road serves one mine only?” Why, indeed?

This salvo apparently found an audience, for it triggered talks between the two counties once again, with agreement to build over Lookout Pass. Thus began a seven year struggle, political and financial. Funds from two counties, two states, and the U.S. government (via the U.S. Forest Service) had to be found.

Idaho’s Shoshone County Board became a stumbling block. Three years of appeals by businessmen, Montana’s new Mineral County, good roads boosters and Yellowstone Trail representatives were not acknowledged. The threat of losing the Trail and its transcontinental traffic did not budge them. The thought of 400 feet lower elevation with less snow did not impress them. Mineral County jumped to its own defense, attacking its neighbor with headlines:

- MINERAL COUNTY BATTLES FOR THE BEST ROADS. Looking to the Interest of Tourist Traveler in Summer Time

- SHOSHONE COMMISSIONERS BLOCK IMPROVEMENT

- SHOSHONE COUNTY BOARD BLAMED FOR INDIFERENCE SHOWN TOWARD HIGHWAY

Mineral County insisted that it could not move forward unilaterally until the Shoshone County Board “got behind” the idea. Finally, the election of late 1918 created a more accepting Shoshone County Board.

By 1919 each side of the summit had been surveyed and engineers had tramped repeatedly through the forest to suggest a route. Idaho would build eight miles to the summit and Montana three miles, so most of the decisions rested with the Idaho delegation.

Wesley Everett suggested one route, others were suggested. A definite route had not been confirmed until the summer of 1920. From the summit, the road would travel west down to the “flats and Willow Creek” and enter Mullan on Friday Rd. and River St. Going east, the new road would descend down to join the Yellowstone Trail at Taft. W. J. Hall, Commissioner of Public Works for the state of Idaho, suggested that the road be less wide than the standard 18 feet near the top, which would have required deep digging from the hillside, and then widen the road later. The idea was adopted for it would save money and time and would meet state standards later.

A fracas arose in September of 1921 when Mineral County announced a proposal from the federal government to join the county on a 50-50 basis, which, unfortunately, would

delay progress on the road for nine months. Shoshone County objected with a headline.

- BOARD OF TRADE TO INVESTIGATE MINERAL COUNTY ROAD

Financing Lookout Pass Road

The reporting of the finances of the project became comical. Figures varied daily. Shoshone County estimated in 1919 the cost to be $33,000 from the state, $66,000 from Shoshone County, $100,000 federal aid and $200,000 from bond issue. In 1921 a five mill special levy was passed in Mineral County; $20,000 was the estimate needed. In November of 1921 Mineral County was quoted as saying “Contrary to public understanding, this road is being constructed by the Federal Bureau of Public Highways of the Department of Agriculture. The forestry bureau has nothing to do with the work, nor has the state of Montana nor Mineral County.” The reader is left to assume that the five mill levy was insufficient and that federal aid was granted.

In Idaho, there was divided opinion about the funding of the Lookout Pass road at the expense of the Fourth of July Pass road, an equally necessary road if the Yellowstone Trail was to succeed as transcontinental.

The Mineral Independent reminded readers of the financial problems of Mineral County on January 17, 1924, a topic that should have been addressed seven years earlier to garner more patience from Shoshone County:

“The land in Mineral County is principally owned by the federal government, in a forest reserve, and the road burden is thus placed upon a few who are actual taxpayers. It is claimed that about 92% of the land in Mineral County is in reserve by the government, and thus exempt from taxation. In Mineral County there is [sic.] over 80 miles of main traveled road through this forestry-owned territory which has been built and maintained by the taxpayer.”

Headlines, richly textured with promises of imminent action, kept the issue on the front pages.

The Wallace Board of Trade was forever conferring with the two county boards, inspecting the progress of the road and issuing false hopes of immediate completion.

For instance:

- LOOKOUT PASS ROAD TO BE FINISHED BY NOVEMBER 1 (1921)

- LOOKOUT PASS ROAD TO OPEN THIS JULY (1921)

- NO SNOW SHOVELING NEEDED [Note: Wrong! Volunteers were sought in April, 1925]

There was great interest in opening Mullan Pass each spring, well, summer, anyway.

While this is a poor picture, you can see a couple of men sitting on the railing of the short bridge (culvert?) across from the other railing on the lower left. Three fellows are standing by the auto, probably deciding whether it was worth it. All are equipped with shovels. And the auto does have chains on. The bleak landscape is undoubtedly due to the great 1910 fire and resembled much of the area.

Butch Jacobson Collection,

Mullan Museum

Photo:

“Jack Knife turn” near Mullan Pass

Northwestern Motorist, July 1917

The Yellowstone Trail Association Role

The Yellowstone Trail Association’s role in this drama was two-fold. First, five influential men in the Lookout Pass project were representatives and officers of the Association. They spoke frequently in support of the project. The intense interest of the Yellowstone Trail Association in this project was shown by the on-site presence in 1920 of founder Joe Parmley and President H. B. Wiley. Second, the Trail was extremely important to the several communities affected by this new road. They not only valued it for in-state travel but they saw the Trail Association as a means of bringing the most popular transcontinental highway and its tourists to the county. Many news articles over the years included supportive statements such as “we appreciate the importance of the Yellowstone Trail to our county,” and “the success of the Yellowstone Trail depends upon the construction of a road across the summit,” and “the Yellowstone Trail would at once become the most popular of the northern transcontinental routes.”

At Last! Or Was It?

There was no grand opening, no ribbon-cutting ceremony in July, 1922 when the road was declared more or less finished. But, then again, November newspapers said that it “will be ready to open July 1, 1923.” In 1924 part of the road was still dirt, not even graveled. It had been declared “open” many times since 1921 and always with caveats. Cars had apparently been sneaking over Lookout Pass, perhaps around construction, for at least a year and reporting their opinions. Construction which started with a bang seemed to end with a relieved sigh.

Thanks for Riding with Us

Well, our round trip is over.

Everybody out.

But study the map.

See where we’ve been.

Notice how the trail and I-90 are entwined.

Just Kidding! Keep scrolling down for more, “Trail Tales”!

The landscape dictated the route but it also provided the texture of past times. We can see how America’s transportation changed: wagon roads for the military and pioneers skirted the Pass; then came railroads which killed all interest in long-distance roads; then automobiles, which brought back the need for highways and opened the Northwest to the automobile tourist and made the Yellowstone Trail a “Good Road from Plymouth Rock to Puget Sound.”

Cataldo Mission

When the light is right, the Old Mission almost looks luminescent standing there serenely on that little knoll in northern Idaho. The Yellowstone Trail ran very near it. You can see it from Exit 39 on I-90.

It wasn’t always painted white and its name was different when it was completed in 1853. Dedicated to the Sacred Heart of Jesus, it was called the Mission of the Sacred Heart. Later it was called the Cataldo Mission in honor of Father Joseph M. Cataldo. Today it is referred to simply as the Old Mission.

Edmund R. Cody in History of the Coeur d’Alene Mission of the Sacred Heart (1930) records the many trials, travels and tribulations that the French Canadian Catholic fur traders, the Iroquois and the Coeur d’Alene and other Native Americans had had for about 20 years to get the “Black Robes” (priests) in their midst. Finally, Father Peter DeSmet arrived in 1839, followed by other enthusiastic Black Robes, all ministering among the Indians throughout the Northwest.

A mission had been built on the southeastern end of Lake Coeur d’Alene along the St. Joe River but its waters frequently flooded, so a site for a permanent mission and church was sought. The knoll upon which it has stood for about 167 years was a fortunate choice. Today, the church can be seen for some distance around, its white exterior framed by the dark of the evergreen woods.

It was DeSmet who designed the beautiful edifice in 1848, but the job of building it fell to Father Anthony Ravalli, a long-experienced missionary. Cody wrote,

A heart less courageous than that of Ravalli must have quaked at such a prospect. For tools he possessed a broad axe, an augur, some ropes and pulleys and a pen knife. For workmen he had two Brothers and a band of untutored Indians.

Fortunately, Ravalli had some experience in mechanics and had an understanding of mathematics and Native Americans. Some “exemplary Christian Indians” were permitted to help in the building. It was they who felled trees and carried rocks from the hills.

Cody describes the building process of 1848-1853 thus:

Plans for a church 90 feet long, 40 feet wide and 30 feet high were drawn by Ravalli and were faithfully followed. Uprights about 18 inches square and rafters about 10 inches square were cut from the mighty pines which grew in abundance on the hillsides nearby. The sawing was done in an improvised saw-pit with an improvised whipsaw, and the planing and shaping were done by hand with a broad axe. Nails were not available so holes were bored in the uprights and rafters and they were joined with wooden pegs.

The roof and walls were made by boring holes in the uprights and rafters and interlacing willow saplings and closely woven grasses between them. Over the whole was spread adobe mud from the river bank. Timbers were cut and planed for the floor, and columns made from perfect pine trees laboriously planed, were placed to support the roof of the porch.

The interior walls were covered with heavy cloth. And those cast iron chandeliers? They were made of tin! Two paintings, brought from Europe by the priests and now restored, hang there today. There were some pews, but the Indians preferred to squat on the floor to hear the Black Robes’ messages.

Upon its opening in 1853, the Mission became a center of activity in the Northwest. It was a hospice for immigrants, and a rendezvous for hunters, and trappers. Even Governor Stevens appeared. It was a self-sustaining village, all built with ingenuity and faith.

During the mid-1800s, the tribes grew to mistrust governments, emigrants and white men in general. Attacks such as the one on Rev. Whitman’s mission in Washington were growing. The Black Robes had been preaching peace for decades, but fear that the white man was usurping their native lands prevailed.

When Father Cataldo arrived in 1877 he would have seen the Coeur d’Alene planting potatoes and wheat and doing farm chores around the mission as they had been doing for three decades. That same year the U.S. Government set the bounds of the Indian Reservation and the Mission did not lie within the set limits. The Native Americans were removed from the very site they helped build and on to the Reservation. In truth, they had more right to the Mission than did the European settlers. The Mission was closed.

In 1928 the Diocese of Boise, through the supporting efforts of multiple groups, restored the Mission to become again what it once was. The foundation, floors, 18-inch walls, pillars, steps all were repaired.

And they painted it white.

Today, the Coeur d’Alene still attend the annual August 15th Feast of the Assumption on the lawn of the Old Mission, now a state park. When we last saw it, there was not yet a visitors’ center with a video. There was a volunteer who guided his party of two unhurriedly for an afternoon through this monumental yet simple oldest building in Idaho.

Over the Mountains Following the Mullan Military Road

That hot August 5th, 1914, found the Yellowstone Trail Association leaders and interested representatives at a convention at Montana’s Hunter’s Hot Springs resort, debating the next extension of the Trail (see Trail Tale: Hunter’s Hot Springs). It had recently been established as far west as the headwaters of the Missouri River near Three Forks, Montana, with a spur south from Livingston to the Yellowstone National Park, its namesake. The conventioneers now eyed the formidable Rocky Mountains blocking the path to Puget Sound. There existed no suitable auto road between Three Forks, Montana, and Spokane, Washington. Nevertheless, the motion to extend the Yellowstone Trail to the Pacific Coast carried. The route was unspecified.

A contingency from Great Falls, Montana, was adamant that the proposed extension of the Yellowstone Trail be routed north from Livingston and the Yellowstone National Park to Great Falls, then west to Idaho and south to Spokane. While the founders of the Trail were opposed to that radical idea designed only to benefit Great Falls, they deferred the question “for study.”

In reality, the decision was made indirectly by the State of Montana. In the previous year, Montana had created the Highway Commission with little funding and one Commissioner with one secretary. But the Commissioner immediately began to designate selected roads as State Roads in an effort for the State to improve long-distance auto travel. He announced to the conference that the existing Yellowstone Trail was designated as one of the first State Roads. And further, that a State Road entering from North Dakota was to continue through Butte and Missoula and St. Regis to the Idaho border near Mullan, Idaho. Without discussion the Great Falls proposal ended even though the State route designation west of Missoula was mountain terrain with very few sections of road ready for auto traffic.

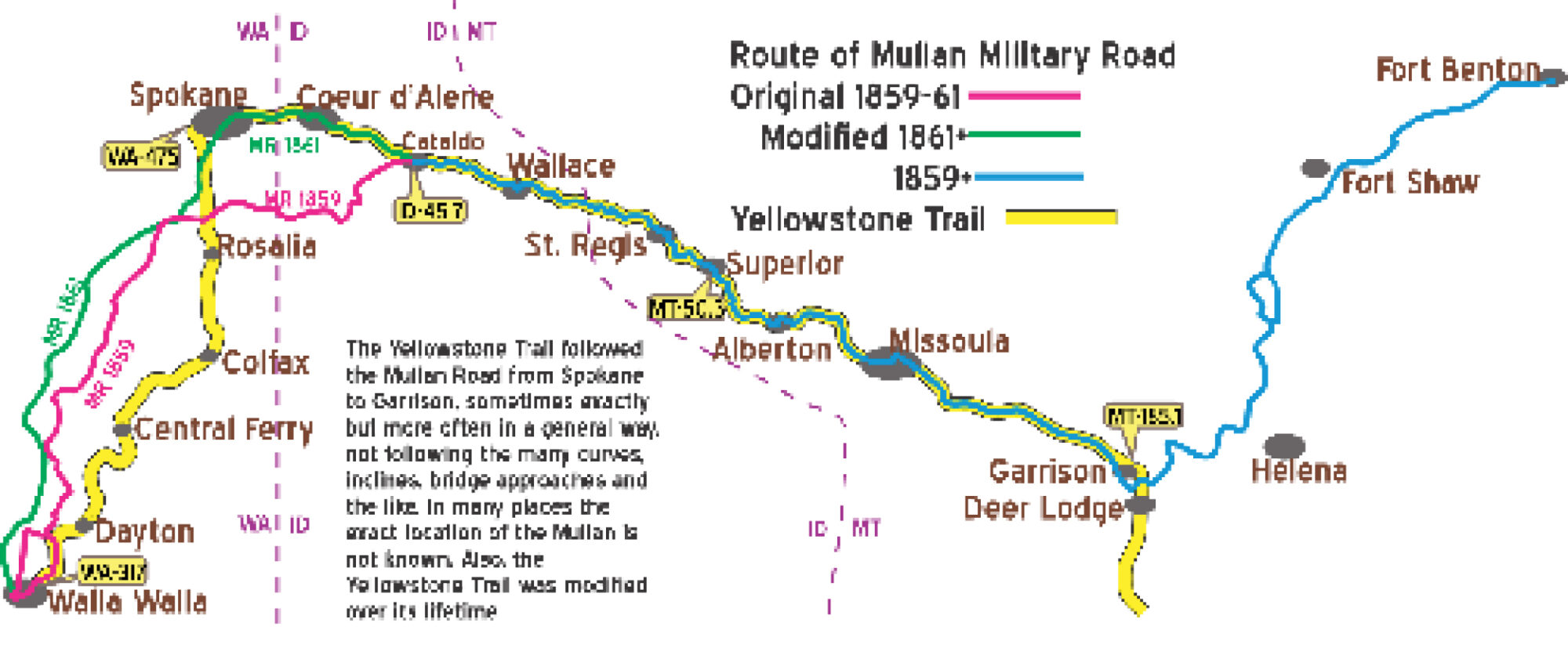

But fifty years previously there had been a wagon road there. The Mullan Military Road had been built between Walla Walla, Washington, and Fort Benton, Montana, including the section over the Bitterroot range of the Rockies to be followed by the Yellowstone Trail. No one mentioned this old road during the 1914 Yellowstone Trail deliberations, no doubt because much of the road was overgrown and many of its bridges over tumultuous rivers were washed out. Only parts of the Mullan Road were usable, those maintained by mining interests and local residents. Bringing together two historic roads separated in time by half a century would be a major task.

Genesis of the Mullan Military Road

An enthusiastic Lieutenant John Mullan, fresh out of West Point, was attached to the 1853 railroad surveying party directed by Washington Governor Isaac Stevens. The survey was part of the great railroad push to open the West. A topographical engineer and surveyor, Mullan was charged with finding a possible railroad route for the Northern Pacific railroad between Missoula and Coeur d’Alene. At the same time, Stevens also realized the need for a wagon road and ordered Mullan to observe for a possible wagon route while surveying for a railroad. From this came a series of exploring expeditions throughout the Bitterroot and other Rocky ranges for Mullan.

Coincidentally, Mullan heard of a potentially feasible wagon route from Fort Benton, Montana, on the Missouri River, proceeding southwest to Garrison, Montana, then west over the Bitterroots to near Spokane, then south to Walla Walla. Almost a decade later he would lead a crew of 100 soldiers and 100 laborers in hacking their way through 624 grueling miles to create that very wagon route.

At that time, in the mid-1800s, immigrants and miners demanded more protection from the Army as they moved west because Native Americans repeatedly hassled and attacked them for invading their land and disrupting their lives. Immigrants arrived at the Rockies from both the east and west. From the east of the Rockies they came by horse and wagon on the Oregon Trail or by boat on the Mississippi-Missouri River. From the west of the Rockies they came via the Pacific Ocean, the Columbia River from the Willamette Valley in Oregon, and then by horse and wagon on crude wagon trails. But Governor Stevens wanted a road available for the floods of new settlers from the east. The Mullan Military Road became that other usable route … however, briefly.

The U. S. Military was told to create the needed road (and pay for it!) so that troops and supplies could conduct the “Indian Wars.” Lieutenant (later Captain) John Mullan proved to be the obvious choice to lead the effort. Although only five feet five inches in height, he was a dynamo. He was described as having a “natural bent for diplomacy and human compassion” and skill as an arbiter, necessary characteristics as he plowed through Native American-occupied country.

On the Road and Over the Rockies

Mullan’s daily records of the 15 month building trek from Walla Walla to Fort Benton (1859-1860) were meticulously kept. Like Merriweather Lewis before him, he noted flora, fauna, latitude and longitude, soil and water conditions, etc. Indeed, today much is known and written about this heroic effort of 160 years ago because of Mullan’s complete notes.

PHOTO: Mullan Road ascending from Alder Creek

-R. H. Dunsmore

For instance, Marilyn Wyse and John Robinson in Roads to Romance (Montana DOT 1992) say that, “… of the 624 miles, 120 were cut through dense forest with an additional 150 miles through open pine forest, and over 100 bridges and river crossings were built. Crossing the Rockies required 30 miles of earth and rock excavation.” It was done with limited equipment and huge human effort.

Mullan and his crew set out in July of 1859 and from Walla Walla to near Coeur d’Alene on the plains the construction was pretty easy going. However, approaching Lake Coeur d’Alene was something different. Maj. Ryan F. Shaw writes that it, “ … required heavy rock work. Descending 700 feet from the plains to the St. Joseph River required felling trees, digging rocks, and blasting boulders. At the bottom the crew was obliged to build a 60 foot bridge … and a 400-yard corduroy across the marshy Coeur d’Alene Valley.” The Mullan Road: Carving a Passage through the Frontier Northwest, 1859-62 edited by Paul McDermott, Ronald Grim, and Philip Mobley. (Mountain Press, 2015).

PHOTO: Mullan Military Road Memorial south of Spokane

Reaching Lake Coeur d’Alene,they built flatboats to reach their supply point at the Cataldo Mission. See Trail Tale: Cataldo. From there east they followed the Coeur d’Alene River which wandered up the winding, steep-sided valley requiring many miles of excavation. Lacking the time to cut a road through all the steep banks, Mullan chose to build many bridges across the river, leaving a “less-than-optimal” road with 41 bridges across the Coeur d’Alene River, and an additional 46 bridges across the St. Regis River in Montana, reported Shaw.

Because progress was unexpectedly slow, when winter of 1859 came Mullan was still west of the Bitterroot Valley. November 8th brought an “outright blizzard,” but they slogged on to about 1.5 miles east of present DeBorgia, Montana, where they wintered in their Cantonment (camp) Jordan. A low rock wall still remains at the site.

Mullan’s letters to Capt. A. A. Humphreys of the War Department from Cantonment Jordan in January of 1860 detailed the severity of the winter to man and animals. Also, Lieutenant James White, the officer in charge of 140 “escorts,” both civilian and military, reported that “October brought four weeks of incessant rain which rendered our road very … muddy and very nearly impassable.” On November 3 he wrote, “The snow again visited us, falling to the depth of fifteen or eighteen inches.” After seven consecutive days of snow, a cold front hit. The temperature fell below zero and they were without warm clothing, their supply pack train having been cut off by the snow. John Strachan, expedition civilian member, wrote, “Cattle, horses and mules lay dead in every direction. Hundreds of car cases dotted the banks of the stream where they had gathered for water and dropped from fatigue or starvation.” These revealing details were reported in John Mullan: Tumultuous Life of a Western Road Builder by Keith C. Petersen (WSU Press, 2014). At the end of February Mullan ventured out to Fort Owen, 60 miles southeast and 30 miles from Missoula. The “civilized” Fort and the Flathead Indians provided Mullan with emergency supplies.

The last 55 miles of construction, from Sun River to Fort Benton, was a welcome level prairie with few streams to cross. On August 1,1860, the Mullan Road reached Fort Benton. Soon after, Mullan returned to Walla Walla escorting 300 soldiers along his road.

May of 1861 found Mullan and party once again headed to Fort Benton on his road to repair, widen, and generally to make it more wagon-friendly. In the previous year Mullan had built the road south of Lake Coeur d’Alene. That proved to be a mistake; it crossed many bogs and streams. This year he corrected the route to pass north of Lake Coeur d’Alene, through the present city of Coeur d’Alene. See Mullan Road map on the next page.

That 1861 route through Idaho gave a section of the road a name: “4th of July canyon.” Mullan and his crew took the day off from felling trees, grading, and re-bridging in order to honor the holiday. They fired their guns, raised the flag and got double rations. Mullan carved “MR July 4, 1861” (for Military Road, not Mullan Road) into a pine tree which remained there for 101 years before the tree top blew off in 1962. It was repeatedly repaired but was finally taken down in 1988, the blazed note preserved in the Museum of North Idaho in Coeur d’Alene. That mountain pass and adjoining canyon are still called 4th of July. A plaque marks the location of the tree. (In Mullan Road Hisorical Park , near ID-30.3)

Randall A. Johnson, in HistoryLink.org (Essay 9202) wrote,

For all its drawbacks and its comparatively short life, the road was a resounding success.

Travelers couldn’t wait to start using it. Estimates made at the time indicate that parts of the road were used by 20,000 people, including Indians, during its first year. Six thousand horses and mules, most of them pulling freight wagons, used the road, as did 5,000 head of cattle. Also listed were 52 light wagons and 31 heavy immigrant wagons.

Gold seekers, mule trains, and immigrants did use the road, stimulating some road maintenance, but after three years the Army gave up maintaining it, turning it over to local residents who maintained it to a degree around towns and for the many mines in Idaho.

Enter the era of the railroad. The joining of the Union Pacific and Central Pacific railroads in 1869 and the building of the Northern Pacific railroad soon outpaced wagon traffic. Even a slick road surpassing Mullan’s wildest dreams would not eclipse the roar of the iron and the Mullan Road declined in many places to obscurity.

The Yellowstone Trail and the Mullan Military Road

Mullan had found a good route for a road over the northen Rockies and had set the route followed, generally, by much of the Yellowstone Trail, US 10, and I-90.

But in 1914 when the Yellowstone Trail arrived, it was in no condition to carry automobile traffic.

Remaining tree stumps that had once been satisfactory for higher wagon wheels were impossible for the auto to straddle. Not even Fords. Autos had to ride the rails in 1913. A driver from Wisconsin found they had to build bridges, cut through windfalls, drive up creek beds.

Much of the alignment of the Mullan Military Road is hard to find today.

Many of the wooden bridges in the mountainous areas were washed out repeatedly by spring floods, and time allowed forests to reclaim land. Some modern roads are on top of the original alignment.

By 1900 some railroad track had been laid directly on the Mullan Road, making it hard to identify. Today, between Garrison, Montana, and Spokane, documenting the alignments of both the Yellowstone Trail and the Mullan Road and determining where they are the same is an exciting challenge, with many unanswered questions.

They danced together, those two historic routes, sometimes moving to their own separate rhythm, sometimes clinging closely for survival. See map above.

The Legacy of the Mullan Road

“So what” you ask? Why care about something that is no longer?

Actually, Mullan’s road did matter and now is an important part of the history of the Northwest.

It was seen as an alternative to the Oregon Trail, as a trade route, and as a path for gold seekers, many of whom stayed to man the mineral mines which built Idaho. People no longer had to go west to catch a boat to San Francisco in order to catch a stage coach to go east. It also established the route to be followed by the Yellowstone Trail. Crude as it was, the Mullan Military Road personified an open door to the larger West.

In parts it ultimately became the Yellowstone Trail, then a four lane highway in the1940s, then I-90 in the 1960s. It must be a good routing.

Exact alignments of many sections of both the Mullan Military Road and the Yellowstone Trail are not well documented. And there are many places where the Yellowstone Trail diverged from the Mullan both for small and long distances. An Internet search can yield reports of current research progress for the Mullan Road.

MT-079.4: A significant section of the Mullan Road is preserved as the The Point of Rocks trail, just north of I-90 west of Alberton, but it takes some navigating to get there. Traveling east or west, from I-90 Exit 75, the west Alberton exit, follow the North Frontage Road 1.7 miles to the west and turn up Mountain Creek.

Almost immediately, the West Mountain Creek Rd. passes between old Milwaukee Road bridge piers, turns left into a former gravel pit and follows the railroad bed another mile to the trailhead at a small parking loop. This is a great place to explore the Mullan Road and the old railroad.

Our map link (above) takes you to the gravel pit where you turn left and proceed 1 more mile.