The Yellowstone Trail and the Yellowstone Trail Association Story

The Yellowstone Trail is a named automobile route across America “from Plymouth Rock to Puget Sound.”

It was named instead of numbered because route numbering, well, it just wasn’t done then.

The total lack of usable auto roads and the general incapability of autos for a long-distance trip may explain why!

Roads had been established by the repeated use of horses and wagons. Mostly packed earth.

A few miles, a very few miles, of asphalt and concrete showed up but all country roads remained dirt…

Or deep sand…

Or gumbo…

“Get us out of the mud” was the universal cry of bicyclists and motorists at the beginning of the 20th century.

Henry Ford, James Packard, Alexander Winton, Jonathan Maxwell, George Pierce, and Ransom Olds had been rolling out autos to clambering buyers for several years now, but the roads were atrocious!

Henry Ford, James Packard, Alexander Winton, Jonathan Maxwell, George Pierce, and Ransom Olds had been rolling out autos to clambering buyers for several years now, but the roads were atrocious!

State and federal governments would not budge in their reticence to build roads. There was no need, they felt.

Railroads, built at great expense, often government expense, provided extensive inter-city passenger and freight service. And state constitutions had restrictions on “internal improvements” such as roads.

Bicyclists and the new motorists were vocal and persistent.

By 1912 some state legislatures had established state highway departments but with little funding and restricted responsibilities; establishing, building, and funding roads were up to each county or township. Or the local farmer!

Then the world changed.

The years around 1912 saw the beginning of a burgeoning of auto manufacturing and the existing Good Roads Movement, started by bicyclists, meant the time had come to be serious about roads and long-distance routes.

From the annual American production of hundreds of automobiles at the beginning of the century, it rose to 200,000 in 1912, to around 3,000,000 in 1923.

Perfecting the engineering and construction of well designed gravel roads with culverts and bridges and drainage slowly took form.

And old Dobbin lost his stable; stables became garages.

The time had come.

Route-making became a popular activity. Hundreds of roads across the country sprouted route names, often assigned by auto clubs. Cross-country auto drives and races (often on a build-it-yourself-as-you-go road) were receiving great publicity.

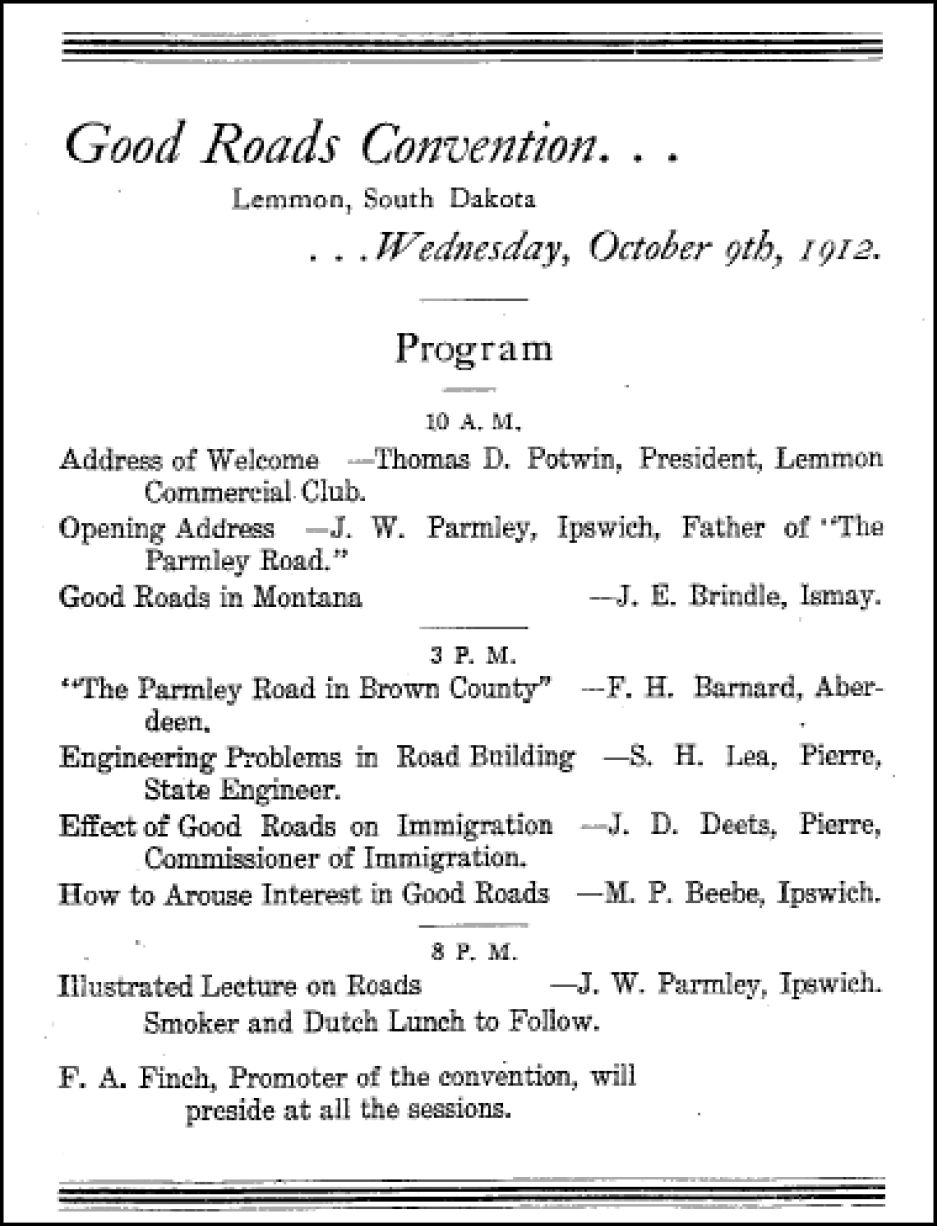

In the South Dakota legislature, Joe Parmley, the hero of our story and Yellowstone Trail founder, had been hooted down and scoffed at in 1907 when he proposed that cash should replace the “labor tax” for county road maintenance. Parmley was so disgusted by the lack of governmental action at any level, and at that wet slough near his home in particular, that he called area men of vision together for a good roads meeting in Ipswich, South Dakota, on April 23, 1912, to do something about the crisis. There had to be a better way.

In the South Dakota legislature, Joe Parmley, the hero of our story and Yellowstone Trail founder, had been hooted down and scoffed at in 1907 when he proposed that cash should replace the “labor tax” for county road maintenance. Parmley was so disgusted by the lack of governmental action at any level, and at that wet slough near his home in particular, that he called area men of vision together for a good roads meeting in Ipswich, South Dakota, on April 23, 1912, to do something about the crisis. There had to be a better way.

At that April meeting of the founders of the Yellowstone Trail, an exuberant attendee called out a potential motto for the route: “A Good Road from Plymouth Rock to Puget Sound.” It hit the newspaper and it stuck. And it pretty well determined the nature of the next eighteen years of the work for the group.

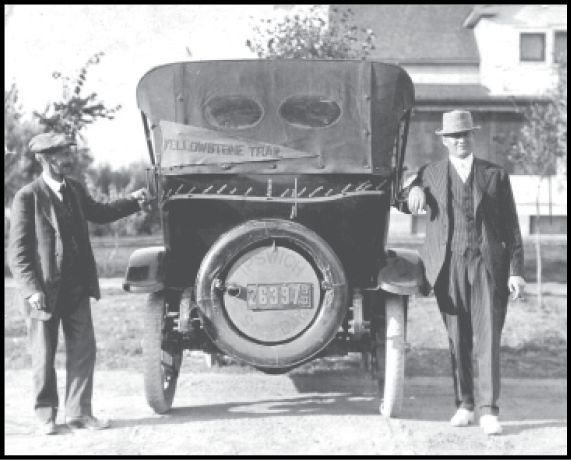

President Parmley and Treasurer Smith with the

“Original Yellowstone Trail Car” decorated with the YT route

Phyllis Herrick

The route’s end points were fixed and the general route was established. And the ambitiousness of the project was tacitly accepted.

The press called that wet April meeting just another Good Roads Association group. Such groups had been formed in countless towns across America. But mostly they were just preaching to the choir.

Actually, this group in Ipswich was more than a Good Roads meeting. It was the beginning of the formation of the Yellowstone Trail Association.

This Association became a massive effort to get a “Good Road from Plymouth Rock to Puget Sound” routed, marked, and made into driveable condition, county by county between Boston and Seattle.The creation of this Association would eventually affect a million or more people who would drive at least a few significant parts of those 3,600 miles in those 18 years – 1912-1930.

The Yellowstone Trail Association was an organization dedicated to giving autoists a better road upon which to travel and a marked route to follow. There never was the intent by the Association to build with pick and shovel, or even improve roads all across the country. The intent was to establish a route across the country on the best roads available and then to promote those improved roads. Usually, the Yellowstone Trail designation of a road motivated improvement. When better or more efficient roads were found by the locals, the Trail was so re-routed.

It was a pioneer of the highway era. Specifically, it initially hoped to establish and map a route along existing roads from the Twin Cities in Minnesota to the Yellowstone National Park [later from coast to coast]. It would advocate for good roads by influencing road construction and by urging financial support from various levels of government. It would attract and motivate tourist traffic to boost economic development in the towns along the route. This last vision of establishing a transcontinental route seems quite forward-thinking when you realize that these founders were from very small towns and seemingly inexperienced in acquiring the resources needed for influencing national issues.

Very shortly after its birth, the Association spread 100 miles west from Ipswich to Mobridge in June with a Sociability Run of 63 autos and the state engineer, crossing open fields, mapping a route. October found them in Lemmon, South Dakota, 120 miles still further west where they formulated the Twin Cities-Aberdeen-Yellowstone Park Trail Association [later shortened to just Yellowstone Trail Association].

The Yellowstone Trail became one of two of the longest lived, most well known coast-to-coast routes, both beginning life in 1912-1913. One was the Lincoln Highway between New York City and San Francisco begun by major Eastern industrialists with correspondingly major financial backing measured in millions of dollars and corresponding publicity experience. The other was the Yellowstone Trail from Boston to Seattle, begun by businessmen of very small South Dakota towns, with financial backing measured in hundreds of dollars and each accustomed to placing ads in their local newspapers. Both began with an effort to build good roads, moved to establishing a known transcontinental route, incorporated a significant effort to promote travel on their route (with its economic development goals) and ended with the coming of universal route numbering by government agencies and the devastation of the Great Depression.

Each chose their name carefully and with skill.

The Lincoln Highway chose to commemorate President Lincoln, thus generating an immediate public sense of familiarity and good will.

The Yellowstone Trail, to arrive at the West Coast following as close to a straight line as possible, would go near Yellowstone National Park, an American feature well known and admired. Thus, the founders chose to “borrow” the Park’s name which had immense good will, positive feeling, and excitement in the public mind.

The name “Yellowstone” at once paid homage to and gave direction to the park.

Then They Hired Hal Cooley

The small Land Office of Trail founder Joe Parmley in Ipswich is still there on Main Street. Word has it that the back room served as a morgue for a day or two when a body showed up in the back yard.

This office served as the national headquarters of the Yellowstone Trail Association from 1912-1916, the one typewriter and telephone doing double duty for the Association and Parmley’s Land Office business. Then they hired Hal Cooley away from the Aberdeen Chamber of Commerce. Ambitious Cooley moved the office from sleepy Ipswich to bustling Aberdeen, 26 miles away. Two years later, 1918, Cooley moved the headquarters to the Big Time – Minneapolis – where it stayed until the Trail’s demise 12 years later.

Cooley built the Association, but he was not alone, although he tended to think so. In a 1924 interview for the Stevens Point (WI) Daily Journal, Cooley was quoted as saying, rather self-servingly, that when he joined the group, “I found that the Yellowstone Trail existed only as an idea. It had no nucleus of organization or income. It was a picture in the mind of individuals and no machinery to make that picture come true. I changed all that.” However, he did see the unique goal of the organization as that of selling automobile travel as a commodity and strove to implement that business plan for 14 successful years.

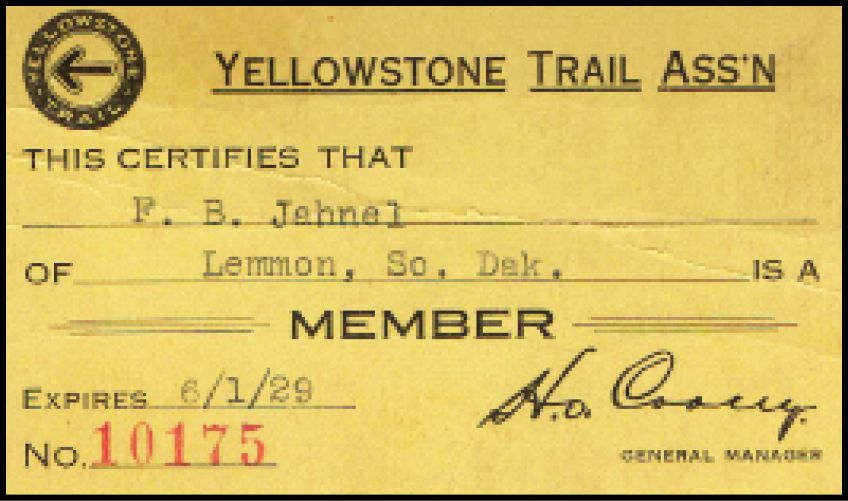

The organization chart of the Yellowstone Trail Association would show national officers at the top. General Manager (Cooley) and an Executive Committee, made up of one representative from each of the 13 states through which the Trail ran, would be next. The Director of Touring Bureaus was another important officer. There was also a Field Representative who traveled to raise funds to help get bridges built. Lower on the chart would be the state chapters and officers and local Trailmen who kept a responsible eye on local conditions. Lastly, there would be the growing list of members, 8,000 at their peak. The members had a vote in the organization, and state chapters had influence in state Trail affairs, but the de facto last word in deciding national issues such as the Trail route would come from the national president and officers. It was quazi-democratic.

Their success, which was remarkable, depended upon the membership and county boards sharing the vision of long-distance auto travel. People had to realize that a long-distance route was a joint effort among communities. The Trail would bring visitors into your community, but also take visitors to the next. This brings about state and national thought as applied to highways. The Yellowstone Trail Association offered an agency through which this national thought could be expressed. The Association had to take ownership of the idea of “unity” across the miles.

“But regional identity does not develop in a vacuum. … it existed within other perceptual categories, material realities and time, whether as is part of a nation, economic system or geographical entity,” wrote Katherine Morrissey in Mental Territories: Mapping the Inland Empire (Cornell University Press, 1997). It was this regional identity problem that the Yellowstone Trail Association had to overcome to sell a transcontinental route.

One hundred years later it was this same regional identity problem that your authors faced from a Convention and Visitors Bureau (CVB) director. Thus, she would not support the idea of a new Yellowstone Trail Association because an advertised Trail “would take people away from her community.” She did not see the promotion of the Trail that would bring people to her community.

To combat this spotty parochial attitude, the original Association ran a long article in the Aberdeen (SD) American and elsewhere in 1920 explaining, in part:

Now there are 2,075,000 miles of highway in the United States. If we tried to build all of them at once, the money is scattered so thinly that the result is practically waste. If by reason of a long national highway connecting up state after state, city after town in a continuous line enriches the country, a road might be raised and give special significance to each community, then a national and logical starting place for a road improvement program is provided, and that is the purpose of the Yellowstone Trail Association.

It must be said that the immediate effects of the presence of the Yellowstone Trail and other trails were probably first felt by those in small, rural hamlets. All were subsumed by the larger choices available in bigger, near-by communities and made available to hamlets by better roads. The local gathering sites were disappearing: the one-room school, the rural church, and the chats over the pickle barrel at the village store. By 1924 with the advancement in truck transport it was claimed that good roads for trucks created competition which kept railroad freight rates down, but also kept trains from stopping at small towns.

They Weren’t In it For the Money

The Association was a non-profit, grassroots group with none of its earnings going to any member of the organization other than the General Manager, the expenses of the Field Representatives and, we assume, the travel expenses for officers to attend Yellowstone Trail Association meetings and fact-finding missions across the country.

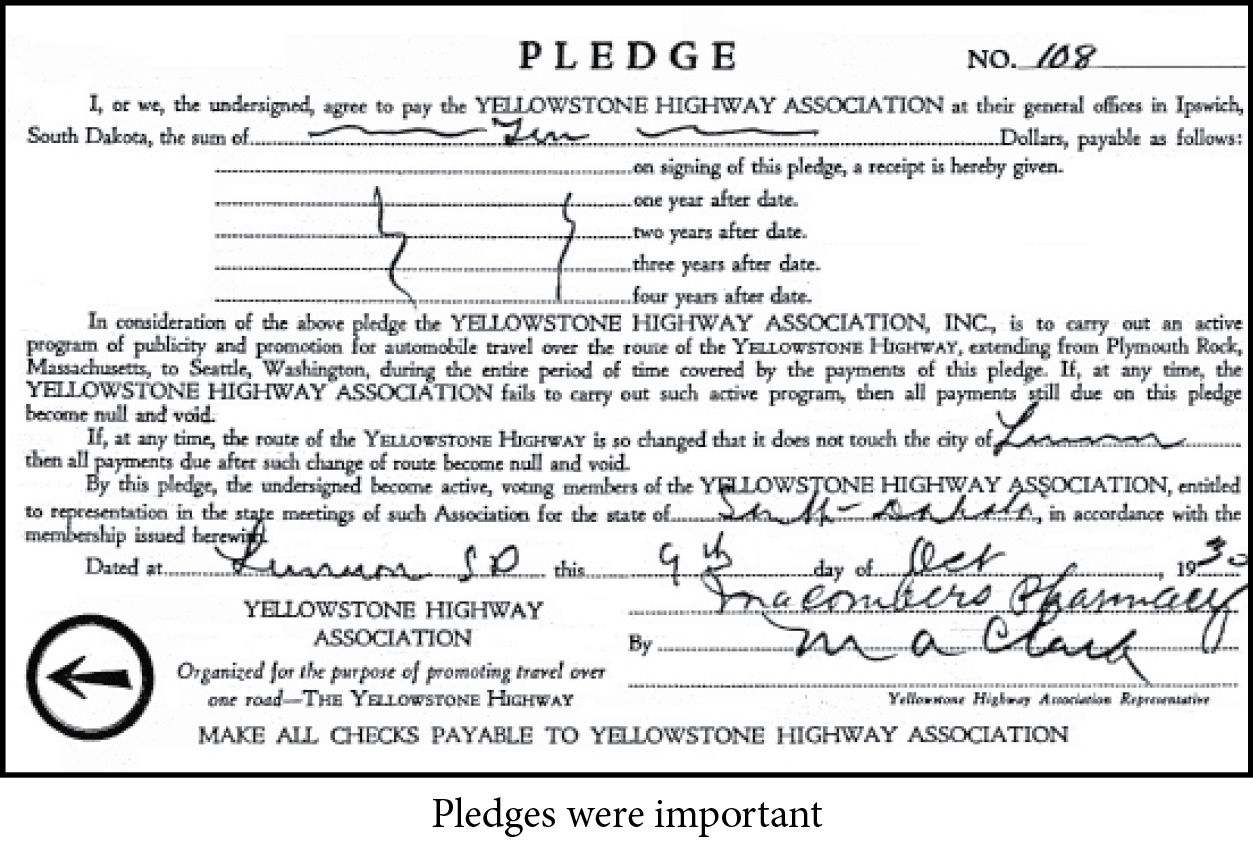

The Association recited compelling arguments for counties and states to create sentiment for road improvement along a single road; then the Association created auto travel over that road. Groups such as Commercial Clubs (predecessor to Chambers of Commerce) and fraternal and business organizations, town boards, county boards, and individuals would provide Association membership funds for promotion through the annual dues.

Dues varied over time and size of town. In the early days, individuals paid $1.00 a year, smaller towns $25.00-$50.00. Large towns paid around $1,000. Getting groups to actually cough up their assigned dues fell to Hal Cooley, General Manager. Over the years, as the importance of the Trail became realized, towns sometimes donated more. Billings came up with an extra $4,000 at one time. However, many towns frequently fell in arrears.

The reading public may have thought that the Association was very solvent when it read the Association’s repeated reports that they had “raised” money for road projects, declaring sometimes at a year’s end that they had raised many thousands of dollars in total for that particular year. By such reporting, it could have appeared to the reader that the Yellowstone Trail Association actually raised and donated those vast funds to road projects. In reality, they had only persuaded towns and counties to spend that much on road construction out of road tax dollars.

That ploy may have been misleading the public, although the figures did announce the persuasive strength of the organization. It was a highly moral group. They turned down bribes proffered by cities to be put on the Trail, and were scrupulous with their meager funds.

What They Did With Their Funds

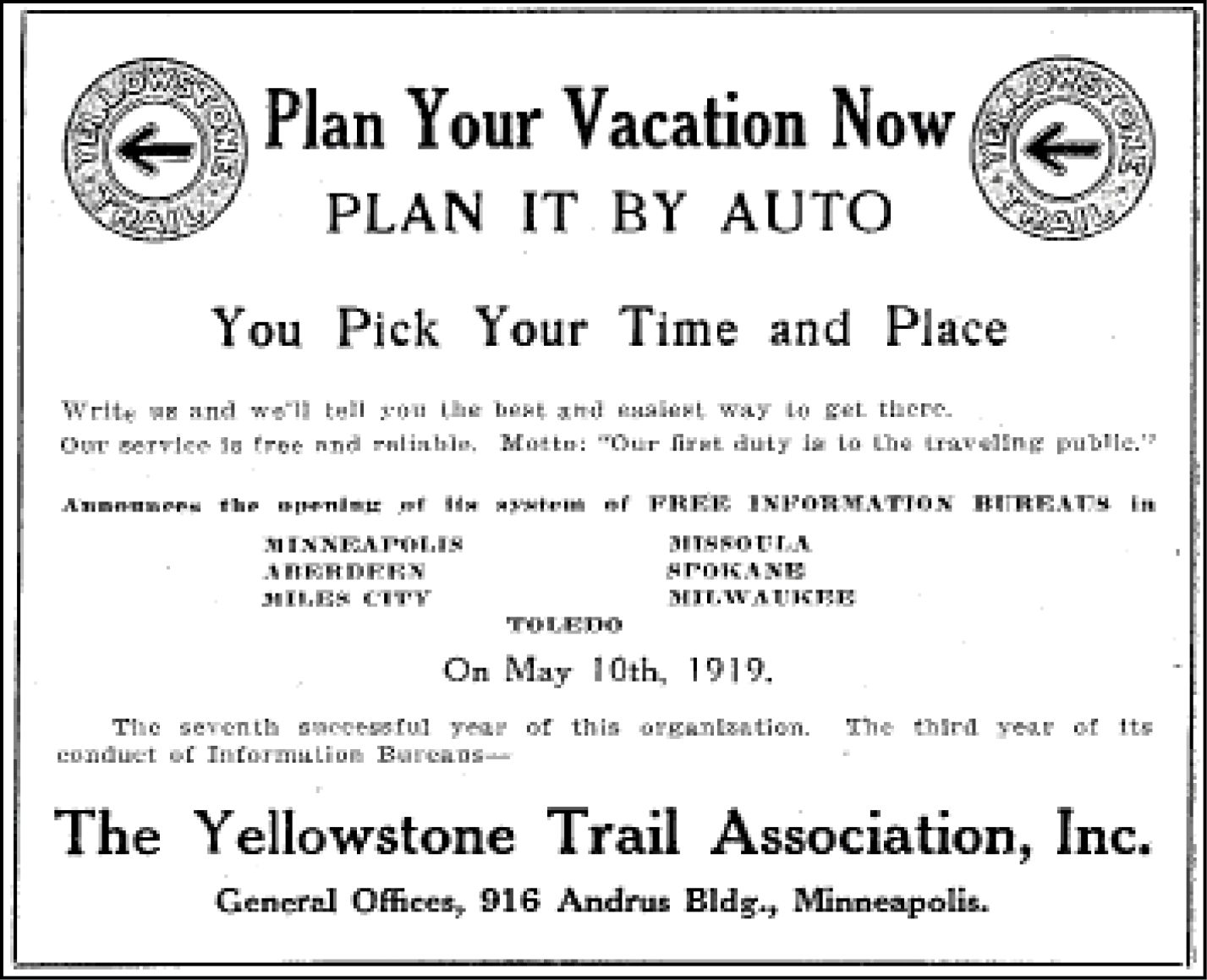

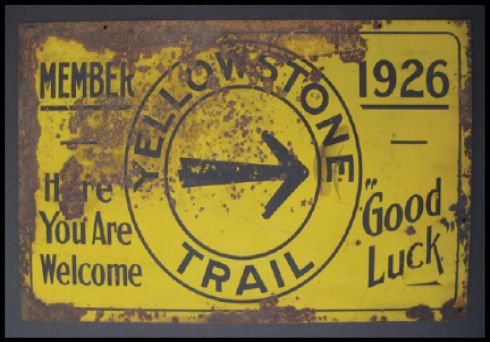

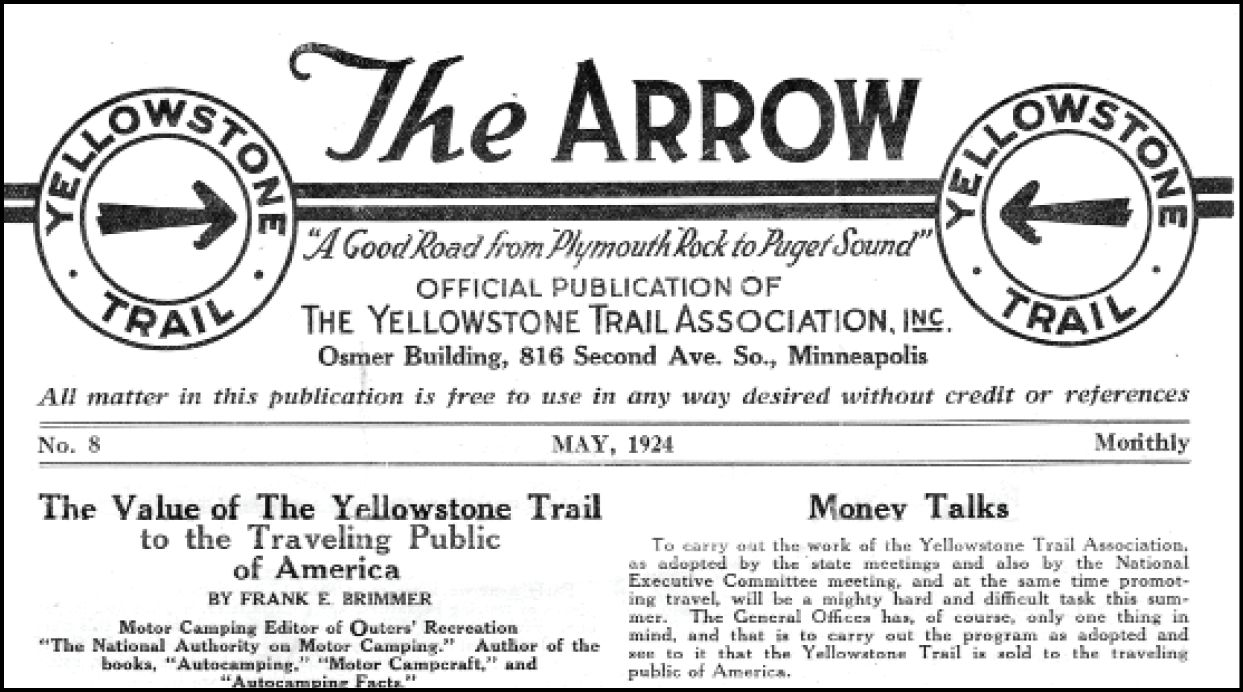

With these dues, the Association created intensive membership drives, publicity campaigns and Tourist Bureaus. On the micro side, yellow paint by the gallon had to be distributed to towns to paint everything in sight along the Trail. Metal signs by the thousands had to be made. See Trail Tale: Signage, page <?>. A blinding number of pieces of literature was freely handed out from their Bureaus and also sent to boosters for distribution. And there was the newsletter, The Arrow.

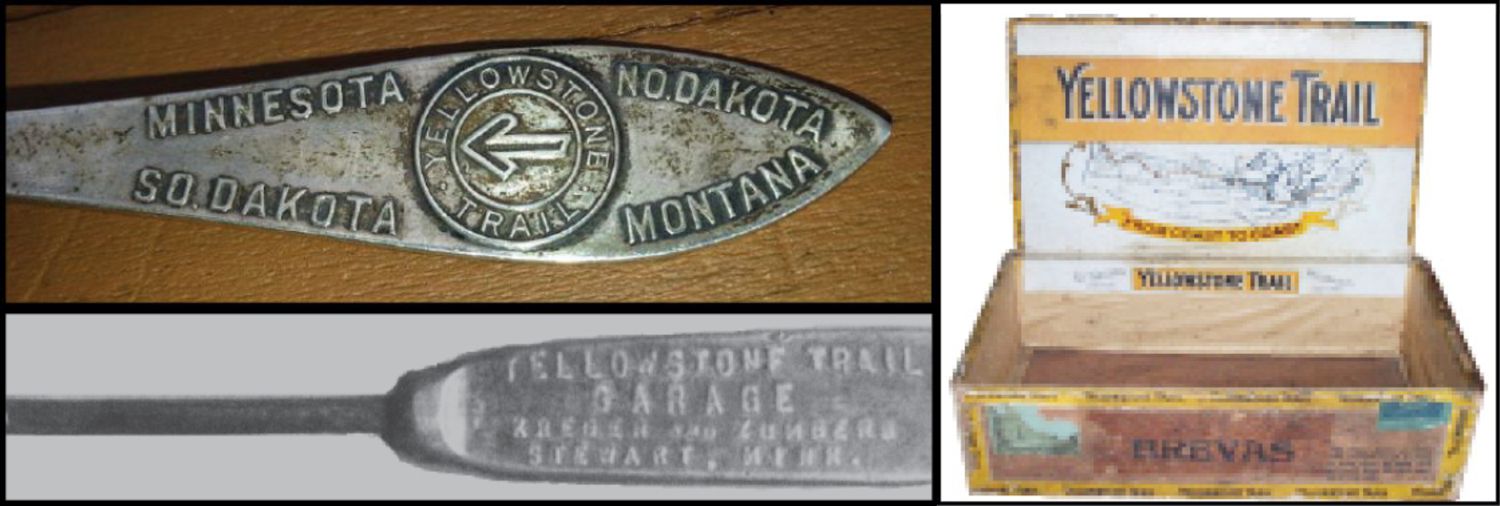

In 1922 alone, 375,000 maps and Route Folders were given away as guidebooks. And, of course, there was postage; even penny post cards add up. No email! In a later year over a million such pieces of literature were given away or mailed. Businesses did their part, too. Spoons, screw drivers, cigar lighters, cigar boxes, and pens were inscribed and used to keep the name of the Yellowstone Trail at the forefront.

On the macro side, support for relevant national road issues was essential, resulting in their membership in the National Highways Association which spoke with the united voice of many trails. A perceived “strength in numbers” move, perhaps. Allowing autos into the Yellowstone National Park was high on the Yellowstone Trail Association’s agenda of support from early on to 1915 when the movement succeeded. The Association was also vocal in supporting the proposed Townsend National Road System Bill of 1919 which favored “a comprehensive national policy that would direct Federal funding to national needs for interstate commerce.”

A continuous public relations engine was vital, and visible projects were necessary to keep the Trail in headlines. General Manager Hal Cooley saw to it that articles about the Trail were published regularly in national magazines such as American Motorist, Motor Age, Midwest Motorist and Northwest Motorist. Their chief efforts were their 1915 and 1916 Relay Races. (See Trail Tale: 1915 Race, page <?>, and Trail Tale: 1916 Race, page <?>.) Boosterism was kept paramount. Cooley appeared at all 13 state meetings annually plus many local meetings as a cheerleader (mostly in those towns in arrears of dues payments). Land values along the Trail increased, in some cases by $10/acre, a fact well publicized. Being declared a “military road” in May, 1918, certainly helped lift their profile.

On the local level, annual Trail Days were held wherein hundreds of townsfolk along the Trail pitched in on the same day to patch the Trail. Coverage from an excited press corps resulted. Dozens of members who owned garages named them Yellowstone Trail Garage, giving free advertising to the Association. Local Trailmen were appointed (a coveted position) to keep an eye on the Trail, and to help lost tourists.

Fifteen major Tourist Bureaus and many minor Bureaus were created. With kiosks in major hotel lobbies or smaller places such as garages, and in their main offices in Minneapolis and Cleveland, they functioned like the AAA today, distributing maps, literature, and weather maps. Bureau personnel would guide long-distance travelers to the next Bureau, and so on to their destination.

All done to get a connected road to member towns and to draw tourists along it.

Routing the Trail

In its 18 year career, a guiding rule of the Association was to route the Trail on the most direct roads from Plymouth Rock to Puget Sound (Boston to Seattle) with prominent access to Yellowstone National Park. After preliminary enthusiasm, they quickly eschewed “splendid laterals,” short branches from the major Trail to funnel traffic to the Trail. They were judged to be distractions from the primary goal.

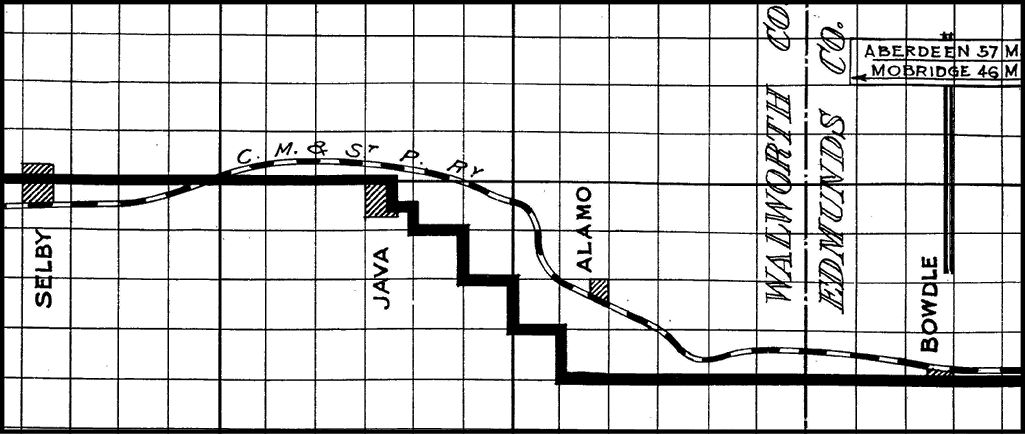

There were many determinants of the route. The dominant long-distance transportation mode available at the time was, of course, the railroad. The railroad close at hand was the Milwaukee Road, at least from Minneapolis to within Montana. Not only had the Milwaukee provided service through Ipswich and Aberdeen, it had in the very recent past actually caused a whole string of towns to be formed from Minneapolis through Baker, Montana. The Yellowstone Trail followed that railroad. Besides, when a motorist broke down miles from a blacksmith or garage he could flag down a train for a ride to the nearest town.

Too often, a usable road was just not available and the Yellowstone Trail Association campaigned for improvements to be made by the locals. Some streams could be forded. Some rivers could be crossed with the help of a ferry. Some hills needed an additional push by the passengers or a friendly driver of a more powerful car that was going your way. Or a horse.

The Yellowstone Trail Association could not do all that was needed to create or improve roads; but it did solve the problem caused by the lack of direction signs. Following the more used fork in the road often worked, but when you missed a turn you had a big problem. The Association started marking the Trail by painting friendly rocks yellow. Near the North Dakota/South Dakota border those “rocks” were eight feet long, ten inch diameter “hoodoos,” naturally formed stone pillars that could be dragged to the highway, erected and painted yellow. Embossed yellow signs with the black circle and arrow of the official logo design were then erected by the hundreds to mark the way.

In the West (that is, west of Ohio) the 1785 Land Survey mandated that land surveys were needed to open the West to homesteading. Space along the section lines was to be reserved for roads. So the Trail followed those mile-long straight roads for a number of miles, made a right angle turn to continue, giving the land a checkerboard appearance. In the established East the idea did not apply nor could it be used in regions with geographic factors like mountains and swamps. West of Ohio many of those right angle turns were abandoned or curved over the years to improve safety and speed. Today, many obviously rounded right-angle turns record the historical use of that local road as a part of a long-distance highway.

Thus the route of the Yellowstone Trail in the center of the country was determined by following established survey lines close to established east-west railroads. Ah, but the two ends to the coasts? The necessary routing there was not too clear.

The Public Land Survey of 1785

The routing of roads from Ohio west is quite different from the original routing in the East.

The Public Land Survey System was mandated since 1785.

In order to organize, divide and sell government-owned frontier lands, the U.S. government, such as it was under the Articles of Confederation, divided the land into grids. Each “township” was a square, six miles on each side, further divided into 36 sections of one mile square each. Each square was composed of 640 acres and could be sold that way or broken down into 160 or 80-acre or fewer subsections.

Cross country farm-to-market roads were replaced by right-angled roads wherever permitted by geographic conditions. This system caused the Yellowstone Trail to follow the many square corners because townships created roads along the grid. Roads looking like “stair-steps” can be found from Indiana west into Washington.

Along routes of heavier traffic many of the right angle turns were “rounded” to facilitate travel. Many a picnic area was established within the cut-off areas.

The Trail Association was relieved of this problem east of Ohio when early 20th century routes followed roads established well before 1785 and were outside of the purview of the Land Survey System. The Rocky and Cascade Mountains in the West also defied a grid system, and all road building there was dictated by geography. •

At the west end of the country, following a line directly as possible toward Seattle, there were usable roads nearly as far as Missoula. From that area to near the State of Washington there were remnants of the earlier 1859-1862 Mullan Military Road. Parts of it were nearly lost, some with newer rerouted roads, and some in useable shape thanks to the mining boom in the area. All of it was hard going or impossible for autos. But the auto era was arriving and many road improvement efforts were in place.

Within Washington the newly created Washington State Highway Department (1905) had big plans for a network of state highways through the state. In 1915, just as the YT was to enter the state, two potential “highways” were being created, the Inland Empire Highway and the Sunset. (See the Washington chapter, page <?>, to see what happened.)

At the east end of the country the destination was mandated by the Association’s motto, A Good Road from Plymouth Rock to Puget Sound. Between Illinois and Plymouth, Massachusetts, however, the founders had “no personal knowledge” of the area. An initial choice of routes made in preparation for its 1916 cross country publicity run didn’t fill the bill for a permanent route.

Changes to initial routings, however, were undertaken when experience increased, and accessible, improved roads became available. Twice the Association rerouted the Trail in a major way, to shorten the route by many miles.

In the East, their first choice was a well-established route hugging Lake Erie, then through central New York and through Massachusetts to Plymouth. They were rejected a permit because of the many marked trails already there. They were forced to route through Connecticut and southern New York for their 1916 cross-country relay race. Not until 1919, apparently after a permit was issued, did a permanent route get established along a line through the larger cities hugging the Great Lakes which would attract long-distance travelers. For a discussion of the route change, see the Massachusetts chapter, page <?>.

The second major change occurred in Washington in May,1925.

The original 1915 route going west used the newly created Inland Empire route. It made a large southern sweep from Spokane through Walla Walla, then northwest to the Sunset Highway over Snoqualmie Pass and into Seattle.

The 1925 route change made use of the improved Blewett Pass, now made useful to autos, so nearly the whole of the Yellowstone Trail then used the Sunset Highway. This move cut 150 miles off of the route but made no friends from along the abandoned route.

The End of the Old Association

The Association and its Trail became very popular in a short time because people saw a possibility of a better road in their area. Towns had fought to be named on the Trail. Visions of tourist dollars had danced in their heads. But the end of the Association loomed ahead both inside and outside of the Association.

The end of the Yellowstone Trail Association in 1930 actually began in 1927. Hal Cooley was hard at work, flogging member towns to pony up their dues and threatening to remove the Trail from recalcitrant towns, a ploy he frequently threatened to marinate the town in dire distress, but apparently never followed through with. Founder J. W. Parmley took exception to Cooley’s hard work. Parmley demanded an audit of the books.

Cooley said the organization didn’t have the $200 for it, etc. Acrimonious letters flew, each defending his management position – Cooley’s on practicality, Parmley’s on loyalty to promises. Their verbal spats and dirty laundry were aired publicly and printed verbatim in newspapers.

In all this posturing, the real elephant in the room was growing. Routes were beginning to be numbered by governments and trail colors would no longer be needed – or allowed. The American Association of State Highway Officers (AASHO) had met with the Federal Highway Department in Washington D.C. in 1925 to draw up the federal highway numbering system we know today. By 1927 the numbering plan was employed by the states; all colors and names would be driven from US highways, replaced by black numbers with the familiar white US shield as background. The various state and county and townships signs followed.

A howl of frustration went up from trail associations. When the battle became futile, Parmley begged to at least have their route bear one single number across. He failed as did others. Sections of the Yellowstone Trail ultimately were numbered with 25 state, 14 US, two Interstate highways and countless county road numbers.

The Trail’s time had come in 1912 and was gone by 1930.

People liked the clarity and efficiency of numbers on roads. They also liked the freedom from paying dues, perhaps forgetting that taxes were “dues.” People had moved on from personal participation. Technology, taxes, and politics had pushed them from the picture. During 1929 and 1930 the Great Depression administered the final blow. •

Throughout the country, roads had been created “by use” to get from one point to another, usually to take farm products from the farm to the railroad.

The United States Post Office was an early user of the railroad for long-distance mail movement.

The institution of Rural Free Delivery required some augmentation of those farm to market roads.

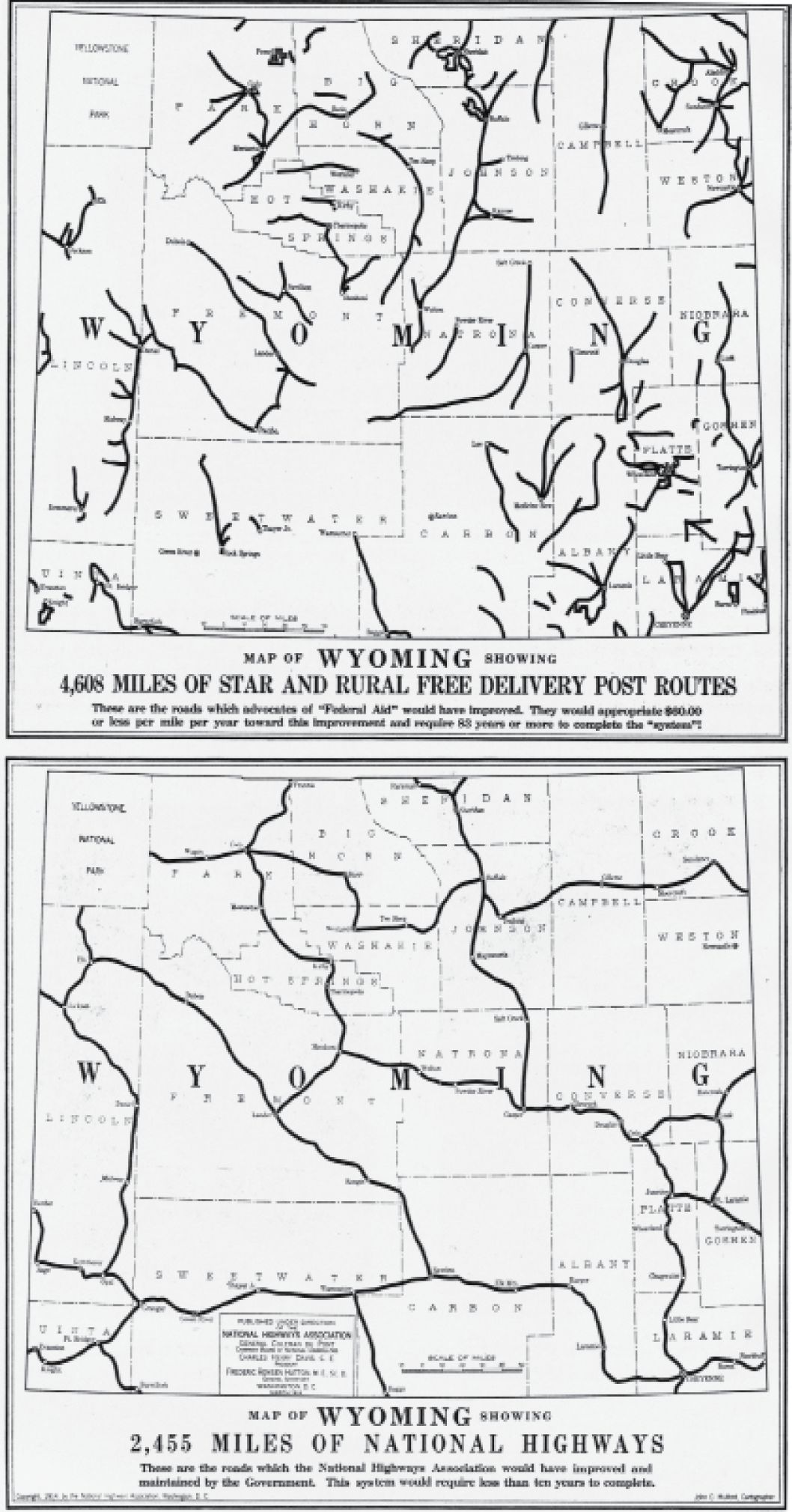

The widespread use of autos resulted in an interest in connected roads to create long-distance routes to give the auto owner wide opportunities. A great deal of ink was used to urge the federal government to fund the multi-use long-distance road.

While the above maps reflect the argument in Wyoming, similar maps and arguments appeared across the country. Proponents of the Yellowstone Trail had no trouble deciding which side of that question to be on. •

The Beginning of the New Yellowstone Trail Association

Around 1999, a number of local historians, several retired university professors, and representatives of the tourism industry, individually and then collectively, began attempts to spread the word about the historical significance, tourism potential, and the fun that could be found in this old auto route known as the Yellowstone Trail.

Those efforts slowly jelled into a modern YTA that is beginning to make its mark.

Today, YTA Members are organized to carry forward this national treasure.